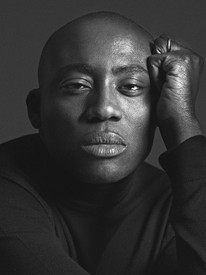

Sir David Adjaye OBE is a Ghanaian-British architect who has received international acclaim. In 2000, he founded Adjaye Associates, which today maintains studios in Accra, London, and New York and runs projects spanning the globe. Born in Tanzania to Ghanaian parents, Adjaye has established himself as an architect with an artist’s sensibility and vision. He is known for his ingenious use of materials and his sculptural ability and his influences range from contemporary art, music, and science to African art forms and the life of cities. His projects range from private houses, bespoke furniture collections, product design, exhibitions, and temporary pavilions to arts centers, civic buildings, and master plans.

Antwaun Sargent is a writer and critic. His writing has appeared in The New York Times, The New Yorker, and The New York Review of Books, among other publications, and he has contributed essays to museum and gallery catalogues. Sargent has co-organized exhibitions including The Way We Live Now at the Aperture Foundation in New York in 2018, and his first book, The New Black Vanguard: Photography between Art and Fashion, was released by Aperture in fall 2019. Photo: Darius Garvin

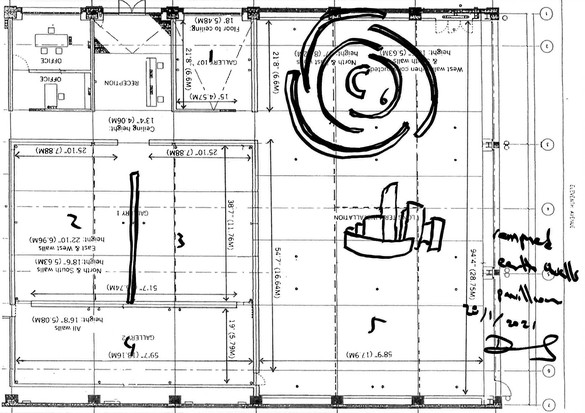

Antwaun SargentFor the Social Works exhibition at Gagosien, New York, opening this summer, you will be presenting Asaase [2021], a large-scale sculpture that takes its name from the Twi word meaning “earth.” This marks an extension in your practice; you’re not abandoning the language of architecture, but Asaase falls squarely within the realm of sculpture, wouldn’t you say?

David AdjayeYes. This project is special for me, I’ve gone full circle. When I started working as an architect, I wasn’t interested in sculpture because I was terrified of a lack of responsibility that I perceived in the practice. I felt that I couldn’t engage with it; I needed something that gave me a certain weight and responsibility to carry. I hadn’t actually matured in myself to carry the weight of my own questions. In a way, architecture became the perfect vehicle for me to find purpose, and also to pursue a certain idea about the world and forms. Thirty years later [laughs] I get to this moment where I’ve built a significant number of buildings, and to make architecture as a young Black male is no longer in question. I no longer have to justify that I can be an architect to any of my clients, or to anybody in the world. That’s just assumed. I feel like I can finally deal with my own questions.

And my questions have always been associated with fragments and the power of fragments. The history of art, the history of Black art, the history of white art—all of it is always this reconfiguring of the creative practice through fragments. I feel like we’re in a Black renaissance right now, and really the optimal issues for me are, How do we learn from the fragments that aren’t necessarily caryatid columns or fragments of Berninian bronzes, right? Rather, how do we learn from the fragments that are our past? And how do we do so without mimicry, because this is not about trying to create a classical; this is trying to reimagine another world. How do we create form with the freedom of an artistic mind, a human being expressing themselves?

My thinking about the fragment is influenced by my time working on a country home for myself in my father’s village, which is my ancestral home in the mountains of Akwapim, Ghana. It’s this idea of constructing from the earth and constructing nonorthogonally, constructing against the urban—constructing organically, one could argue. I’m not interested in the caricature of the form, I’m interested in the essence of the form. In all my work I’m interested very much in the root essence, in the purity of the form, always trying to search for the DNA of the thing. In a world that’s so complicated with production and capitalism, to be able to have the reduction of things as elemental is something I pursue as an aesthetic pleasure. So in a way what I’m talking about right now is the ability that I now have in myself to be at one with the hamlet, the village, and the city at the same time.

It’s designed to create moments where the audience can just sit in-between earth. This is something people have forgotten how to do. It’s a return to a very primal moment.

Sir David Adjaye OBE

ASI think one thing that arises in this work is the materiality of it—the use of rammed earth is significant.

DAI’ve always questioned the way material has a certain language within the classical canon of a European sensibility. There’s an apartheid in that, or a hierarchy of materiality. I find this sense that, say, marble is noble and some other material is ignoble a really vulgar way of understanding the power of materiality. So I’ve just fully embraced this material that’s seen as the poorest material on the planet: earth. For me it’s actually the most profound material, because it’s the material that has sustained our humanity, literally, since our inception. We’re at this moment now of thinking that we can cut away from earth and live in a kind of artifice. Our biophilic relationship with earth—some now think it can be simply severed. How? So I’m deeply invested in reconfiguring the image of rammed earth as a radical twenty-first-century material. I’ve realized that I don’t even mind where the earth is from, it’s just about the earth. Again, it’s about the idea of what is the fragment that actually connects us back to our humanity, and the fragment in a city like New York is just to see raw earth. That’s actually the most radical thing.

ASFor you, then, is this a living sculpture?

DATotally, yes. It’s a way of preserving a fragment of life.

ASHow should it be experienced? What are the possible ranges of that experience?

DAIt works across many modes of sensory perceptions. It will become an atmospheric absorber of a certain kind of moisture in the gallery and will emit a certain atmospheric quality. It will have a kind of presence quality, an aura of form. I anticipate that when one is just still with it, and in reflection with it, it will hold the most power. It’s designed to create moments where the audience can just sit in-between earth. This is something people have forgotten how to do. It’s a return to a very primal moment.

It’s also a sculpture that utilizes perspective. It’s a kaleidoscope that’s changing, so that it’s never what you think it is from any one view, always shifting. And that’s a playful element, but one that I really value. We are polyphonous in our understanding of how we engage with things made, and I want to engage the whole spectrum of the sentient nature of our presence and our bodies with form. So it’s working without the eyes, with the eyes, with the ears, with the nose, and even with the way in which we breathe through our noses and mouths.

Social Works: Curated by Antwaun Sargent, Gagosien, 555 West 24th Street, New York, June 24–August 13, 2021

The “Social Works” supplement also includes: “Notes on Social Works” by Antwaun Sargent; “Lauren Halsey and Mabel O. Wilson”; “The Archives of Frankie Knuckles: Organized by Theaster Gates”; “Carrie Mae Weems and Maya Phillips”; “Allana Clarke and Zalika Azim”; “Rick Lowe and Walter Hood”; and “Linda Goode Bryant and DeVonn Francis”