Alice Godwin is a writer, researcher, and editor based in Copenhagen. An art history graduate from the University of Oxford and the Courtauld Institute of Art, she penned an essay for the exhibition catalogue Damien Hirst: Fact Paintings and Fact Sculptures, published by Gagosien in 2022, and has contributed to publications including Wallpaper, Frieze, Aesthetica, and The Brooklyn Rail.

ALICE GODWINIn C was really born out of the pandemic and the way we were living at the time. I wonder how you feel looking back?

SASHA WALTZIn C actually opened a door. Typically, I work very closely with the dancers and I don’t give the work so much, but with In C we were really sharing the spirit of the piece. It was a tool for transformation.

The lockdown was so gray, so depressive, I wanted to create something that was positive and uplifting, that would remind us of the joy of life and the feeling of being in our bodies and being with each other. I think this is still very valid in the crises we are living through now.

AGIn C explores themes of freedom and democracy, and the relationship between the individual and the group, so it’s fascinating to hear how it’s taken on new resonance and a life of its own.

SWExactly, that’s a good way to put it. The ten original dancers, who are all from different nations, are like ambassadors who can go out and share the piece. It’s like the seeds of a plant that go with the wind and travel to different places, so the plant will multiply. There are so many projects around the world already, in Calcutta and Pune in India, Mexico, Romania, and Holland. In C doesn’t have to have the perfect professional form; it can take different shapes and bring people together.

AGIt’s fascinating to think what might happen when different dancers come together who do not know each other very well.

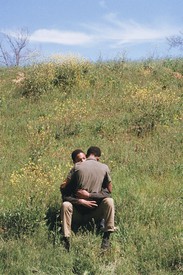

SWI find it so interesting to see how different people deal with each other and function in a collective. It’s like speaking a language when you don’t have all the vocabulary necessarily but you can still communicate.

It’s always inspiring and challenging when new people come in—it forces the dancers to stay open. It should not become a habit, you know? With dance, you can find yourself starting to make the same decisions, but In C is about being in the moment and always being open to change. The mind and the body have to remain flexible, like elastic.

AGWhen I was watching the livestream of In C in Berlin in December 2021, there was an amazing sense of tension between the dancers as they fell in and out of sync. You’ve mentioned the responsibilities of the dancers before; I wonder if these responsibilities have changed as In C has evolved?

SWResponsibility and freedom were two aspects I was very concerned with because the relationship between the individual and the collective was so present. You can only be free if you take into account the needs of society. For me, that is how a well-functioning society should be.

If everybody led, you would fall into unison, like a one-dimensional, unified society. It’s beautiful if there is difference.

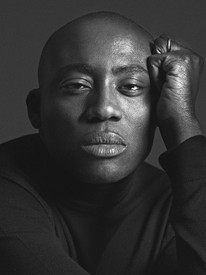

Sasha Waltz

You can transfer the societal obligations that were so necessary in the pandemic to the system of In C. For example, you can do the whole piece alone, running through the movements perfectly, but then it doesn’t work. In C is about collaboration—like society. Sometimes you have to let go of what you wanted or planned. You have to stay open and fluent. If someone comes your way, you can make a choice to change course or go together; maybe more people join and suddenly there is a harmony. These spontaneous unisons, formations, and geometries that appear are magical. The dancers are giving in to something bigger than them—the needs of the group. And that’s what I call society.

What I find really beautiful is everybody is the same. Everybody has the same starting point, the same fifty-three figures, and the same open space. There’s no soloist and choir, and the leader can always change. Some naturally become leaders and want to go forward. Some love to stay behind and take their time. The last follower is as important as the leader who pushes things forward, because they bring the group together. I asked the group to actively respond to these roles. If everybody led, you would fall into unison, like a one-dimensional, unified society. It’s beautiful if there is difference.

AGYou certainly feel the rolling shift of focus. Now that In C is live in front of an audience, there’s the relationship between the dancers and audience to consider. How does having an audience impact the way the dance unfolds and the decisions that are made?

SWIt’s wonderful to be back in the same space with audiences. With live music, the dance is a bit faster than a general heartbeat, but for the public it feels like a heartbeat, which creates a beautiful exchange between the audience and dancers. You know, it’s an exhausting piece because the dancers are continually onstage for about an hour. They fall into kind of a trance that transmits to the public and when the performance stops, we wake up together.

I was also very interested by the concentrated energy of the camera during the livestreams. We entered a magical space through the camera, somehow, where we were connected to so many people. But we definitely prefer to be together. For me, the theater is a bit like a church and the performance is a ceremony in some way.

AGTerry Riley’s original piece of music is essential to all of this.

SWAbsolutely.

AGI know you were inspired by the philosophy and format of “In C.” Have you worked in this way before, beginning with a piece of music?

SWI’m so grateful to Terry and I admire his work so much. “In C” was such an opener in terms of structure. It’s very much a piece about inclusivity and working with community, and now we are really spreading the word or, let’s say, the spirit. It’s also such a generous score because Terry gives so much freedom to everybody who wants to touch it.

“In C” is just two pages of fifty-three musical figures of different lengths. They are executed in numerical order, from one to fifty-three, but each figure can be repeated as many times as the musician wants. For the dance, I created fifty-three movements, and the rules are the same. The dancers cannot be further than four to five movements apart. In the same spirit, I wrote fifty-three spatial rules that the dancers have to deal with as well. The musicians have to listen and create aural space, but the dancers create physical space, and for that we needed more information. The beginning position is clear on the left side of the space. I keep changing the end a little bit, but the dancers pretty much come together and go forward, spread to the edges of the space, and form a line. I felt the necessity to have certain anchors like that.

AGYou’ve spoken about exploring different cultural influences and styles in both the movements of dance and the musical score.

SWWe have an original recording of “In C” with New York’s Bang on a Can, but we have also been working with different regional and classical musicians, like the Mahler Chamber Orchestra. For example, in Rotterdam we invited international musicians to join Bang on a Can, in Oslo we added a female singer, and in Italy we used a local group of jazz musicians.

This is really in the spirit of what Terry wants, that anybody can play “In C.” It has so many different colors and spaces, but the piece stays the piece. Usually when you have a score, there are slight changes with different conductors and different orchestras, but with “In C” each night is a revelation.

AGHave there been any particular standout performances so far or surprising results?

SWThe performance in Rotterdam was absolutely extraordinary. We were thirty musicians and thirty dancers in a gigantic former submarine. The music is so hypnotic with its repetition, but there was something ecstatic about the sound there. It was an almost spiritual experience.

AGThat sounds incredible. The pulsing C provides an anchor for the music—I wonder whether there are any movements that are foundational to the choreography?

SWThat’s an interesting question. In the beginning I needed to explore how the composition worked. We created phrases and then I realized that these phrases were too long. The repetition doesn’t work in the same way. So I cut the phrases apart. Some of them have a head and a tail, and some parts repeat, so you can say they are reoccurring notes in a way, but the same movement is not in every figure.

I found in the beginning that some movements were too stationary, so I added figures that really travel in space.

AGThe speed and pace are interesting elements. You created purposeful pauses and moments where the dancers can catch their breath, but do they also decide when to pause?

SWBoth. I added more quiet or more gestural phrases, but I also included pauses in the counts, and the dancers have the possibility to pause at any moment. It’s very necessary in terms of avoiding collision. If it gets too tight, how do you get out of a trouble?

AGI love that idea of getting yourself out of trouble. Another really important aspect is the light and the bold primary colors of the costumes and scenery. You’ve mentioned the idea of the dancers each wearing a different color, like an identity. How has color played a role?

SWI wanted to do very simple, unisex costumes during the pandemic. I thought, If we are going to travel at all, let’s reduce travel costs and have a costume you can put in your suitcase. And I thought of the colors of the rainbow, like flowers of different shades that fade into one another.

I wanted to foster the same idea with the lighting. I started by asking for fifty-three atmospheres, but in the end I think we actually have more. Through the performance there is a constant change of color, like it’s pulsing. Importantly, we are also improvising with the light. We are following the same atmospheres, but it’s not always the same result as we move through the transitions.

AGThere can be a silence at the end of a performance if the musicians finish their fifty-three phrases before the dancers. I wonder how you thought about that gap of sound?

SWI love silence as well as sound—you need both. I think silence amplifies the sensation of sound and enhances our awareness. When silence appears, I feel the audience hears themselves more strongly, they become self-aware. Silence can be very confronting sometimes, because you not only hear each other and the breath of the space and the performance, but you hear the sounds of the public as well. The silence can become embarrassing, but it connects us somehow. We are not covering up anything.

With In C, I thought it was nice to hear the pulsing of the dancers, the rhythmical sound of the dancers, which goes on even after the sound has gone.

AGDo you have any thoughts about the future of In C and its evolution?

SWWe will keep working with communities, sharing the movements with more amateurs and professionals. For example, in Georgia and Germany people of different abilities have joined professional dancers to form mixed groups. We are also starting a project in Ukraine with dancers from Kharkiv and Kyiv. It’s a bit like folk dance in a way, which I love. At some point, when enough people have learned In C around the world, I would love to do a celebration that echoes how I felt at the very beginning—to celebrate life and being connected. For me this piece talks about what it means to be alive.