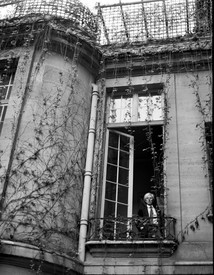

Lauren Halsey is rethinking the possibilities for art, architecture, and community engagement and produces both standalone artworks and site-specific projects. Combining found, fabricated, and handmade objects, Halsey’s work maintains a sense of civic urgency and free-flowing imagination, reflecting the lives of the people and places around her and addressing the crucial issues confronting people of color, queer populations, and the working class. Photo: Czariah Smith

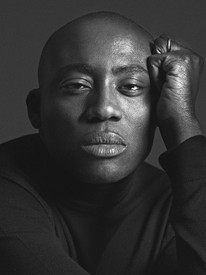

Mabel O. Wilson is professor in architecture and professor in African American and African Diaspora studies at Columbia University. She also serves as the director of the Institute for Research in African American Studies and codirector of Global Africa Lab. She is cocurator of the exhibition Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America (2021) at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo: Dario Calmese

Mabel O. WilsonWhere should we start? Do you want to talk about process, your work, what’s going on in the world?

Lauren HalseyJust a little bit of background on my art practice: I build installations that right now I see as experimental miniatures. They’re human scale, of course, but they’re models for architectures that I hope to build before I die—at least one. The background on that is that I took classes in the architecture department in the community college here for about five years. The icing on the cake in my fourth or fifth year was that we were able to apply everything we learned drawing at the drafting table to a design/build course that took place on the construction field, where we built in collaboration with the construction department. That rocked my world and changed my process forever.

MWCan I ask what you built?

LHYeah, I took the class like four times just to get to that point. It was sort of a competition, and I lost every time. By the fourth time they were like, Just give it to her. I remember designing something that had superwild angles and it basically got reduced to a cube, you know? But for me the one-to-one of doing something with my hands at the drafting table and then getting in the dirt and building it with people I like—it was very special and soulful as a recipe.

After that, I transferred to another school for architecture, and it couldn’t have been more different. Mostly everything became digital and about the slickness of renderings; no demographics around race and class were considered in the project proposals we were given. So I dropped out and went back to the community college, took art classes, and started appropriating what I thought the process of the architect was: mapping, blueprints, models, actual architecture. For much of my art practice I was making blueprints of my neighborhood and remixing city blocks, local landmarks, parks, and homes through a very fantastical lens. I’m still in a model-making phase, and I hope in ten years I’ll actually get to building on the block.

So that’s where I am. It’s been a very long slow burn, of trying to get to it through the back door or the side door.

MWThat often happens. I have a friend, Mike Cranfill, who is a painter and architectural educator. Years ago, when we taught together at the University of Kentucky, he would teach his architecture students painting and life drawing, because architects should be able to see something three-dimensionally, you have to learn to see spatially. Figure drawing is a really good exercise in understanding three-dimensional form in space, particularly a form that’s dynamic. And painting, you know—it’s direct, literally making things with paint and whatever else. The problem with the digital is it’s not material, so you’re never working directly on “the thing,” the building. With architectural drawings you’re making a set of instructions for someone else to build.

LHTotally. I’d been inspired by the free-style building that I’d watched my father do in the backyard with his friends my whole life, and architecture proper was nothing like that. So I thought I’d address it spatially through art, because the rules are different there—if there are any, you know?

MWYeah, artists work directly on the thing itself. There’s a famous essay by the architectural theorist Robin Evans, “Translations from Drawing to Building” [1997]: where he talks about how artists, typically but not always, work directly on what they make, while architects actually work through drawing, we work with a mediated representational mode in order to build. It’s a very different process of making. You’re absolutely right: that direct engagement with materiality, with gravity—you get a very different sense of building when you work that way.

What you just said about your dad in the backyard making stuff seems to be a through line in your work, which is very much about the area you grew up in and the language of the built environment, and how that often translates into ways of building.

LHYeah, absolutely. I sampled collaboration with him, watching him build with his childhood friends—the social way of making something that’s at stake for everyone because we’re all from here, we care, you know. But also being a kid going to Home Depot every weekend . . . it’s sort of wonderful for me that gypsum panels are now my superstar material. I’m figuring out how to transform them into some sort of new form that’s a structural wall but also drawing and collage, and can be aesthetic and sort of stacked like Lego bricks to build an architecture with. That’s what we’ve been doing in the studio, very slowly, so that we can create our own aesthetic skin for the panels.

MWWhat size are the panels?

LHThey’re two by two. But that might shift as the experiment shifts.

MWDo you ever work with found material?

LHAbsolutely. I obsessively archive my neighborhood, and my favorite archives are the informal ones—the hood ephemera, the incense, the oils, the party flyers, the posters, the business cards, the graphic design that folks are making with their hands. My installations either sample them in the form of drawing or engraving, or I use them directly. My goal one day is to build an institution—no, that’s too formal—to build a space to hold these informal community archives. I find it especially important as LA is going through intense development. Neighborhoods are being erased and new migrations are happening. And just trying to hold on to our stuff—

MWYou’re in South Central?

LHYeah. It’s nuts. It’s disgusting. There’s all this development and global investment, you know? Market-rate condos, two stadiums in Inglewood, the trains—it’s nonstop. Folks are trying to hold on, and it’s especially compounded by this time that we’re in. So you see a lot of mutual-aid efforts, a lot of people with neighborhood pride and love trying to show up for here.

MWMy uncle was the artist John Outterbridge, who just passed away. He had a studio over there, off of Slauson, for about thirty years, and his way of connecting to the place was very much about friending your neighbors. I think the neighbors ran a pallet company, so they’d look out for him, he’d look out for them. It was interesting in terms of how community formed there.

LHTotally. It’s the reason why I live and work here. I have to be immersed and in the mix of all of the different street worlds I navigate. I have a community center next door to my studio, but my studio space is also the kickback, communal space for friends, and I’ve found that to be super important. So I’m slowly working on that too.

MWWhat are your plans for the community center?

LHI don’t know yet. For the past year, almost, we’ve been doing an organic-produce-box distribution every Friday in Watts.

MWI saw that. It looks like an amazing effort.

LHI’m literally just taking it a minute at a time, because it’s completely overwhelming. But the function of the community center will be to shapeshift with whatever the needs of the community are at the moment. When everything pans out, I want to open it up to bringing students in and doing super engaging one-on-one tutoring because of how flat Zoom learning has been. Soon after, I hope it’ll grow into a music studio, dance class, art class, whatever it needs to be. Right now it’s a hub and warehouse for produce, which is a lot.

MWThat sounds like a generous act for folks, because people need so much, especially in this time of crisis, which never seems to end. Crisis capitalism. To have a space that can be a conduit to the community, and then try to build around what their other needs might be, would be a really extraordinary project.

LHHopefully you’ll be able to visit one day.

MWI know, if I ever get back out there. When I lived in the Bay Area I’d go to LA just to hang out. It made me happy and felt like home, more so than Oakland. I think there’s something about the history of Black communities in LA, folks who migrated from Louisiana and Texas, which felt very familiar. I just get the sense that for people in LA, anything is possible, they’re not constrained by any convention that building has to be in this style or it has to conform to that concept. The city is a space of imagination.

LHYeah, totally. I think that’s how I discovered my relationships with my best friends, with them as collaborators in art. We were doing a float for the Martin Luther King Day parade and I was out there by myself. It was a fifty-foot flatbed truck in front of my mother’s house and I wasn’t going to finish on time. My friends came outside, headed to their cars, about to leave, and they asked if I needed help. I said yeah, they jumped in, and we’ve been making together ever since. Only in a place like LA could I be working on a fifty-foot float at midnight on the block, using multiple backyards, you know, with all this music, all this fun. There’s a social aspect. There’s space to an extent. There’s just this freedom here. But it’s also not like it’s our utopia, either—there’s a lot of headache and oppression as well.

MWGentrification, policing—

LHOf course. All sorts of forces, yeah.

MWCould you imagine working elsewhere?

LHNot on my scale. It would cost too much money. That was my problem with New York. When I was doing the Studio Museum in Harlem residency, I had a breakthrough with carving and landed on this form of making hieroglyphs of Harlem and South Central. But it was dependent on the architecture of the museum and I was confined to a smaller scale, because of the size of my studio. Which was beautiful—it was by far the best studio I’d ever had—but when I got back to LA, I realized, The sky’s the limit as far as building up here. And because I’m from here, being able to use five backyards at the same time . . . If I was ever going to get to the scale of a building, and away from making an artwork referenced as spatial and just like an actual architecture, I could only afford to do it here. It just became a practical thing. I set up in my parents’ backyard and eventually my grandmother’s. And then it became like utilizing the sun, allowing materials to tan, letting them just do all these things that became part of manifesting the material.

MWIt sounds like the work is very site-specific in that way.

LHAbsolutely, yeah. I always wondered why—and the answer might be obvious, but I don’t know—why are there so few Black architects? Why do you think that is?

MWTo control space is power, right?

LHRight.

MWThat’s why. The spaces we live in, the models of how wealth, land, and property are accumulated, are defined by racial capitalism. Who has access to the land and the wealth determines who gets to build. And that, sadly, is not Black folks. Because whether it was slavery or Jim Crow segregation, or even where we live now, as we can see with policing, the logic is to control our mobility or our ability to actually accrue property, right? Because that’s where power is. I think that’s why it’s made it difficult for Black folks in this country to become architects.

LHRight. Which is why a lot of the architecture I find myself surrounded by feels as oppressive and cold as it does, probably.

MWYeah, you have to know people who have the resources to build—land, money. A lot of architects’ first project is a house for a parent, like Robert Venturi’s house for his mother. And Black people have never been allowed to accrue the kind of wealth to be able to do that. There are less than five hundred Black women architects in the country.

LHWow. That’s nuts.

MWIt’s absolutely crazy. If you look at law, medicine—as those professions became institutionalized in the nineteenth century, and you had to get licensed to practice, it was hard but by late in the century, Black women had broken the color line in those fields. With architecture that doesn’t happen until the 1950s, when the first Black woman architect, Norma Sklarek, was licensed. So it’s very late.

LHDo you find that architects are engaging with the community more in the design process from stage one? I don’t mean community-engagement meetings, or things like that; I mean, for example, having an open-air studio and designing collaboratively with who’s been here, you know what I mean? Sort of coauthoring.

MWI think it depends on the architect. I do think that people are now more aware of the value of working collaboratively, but you know, there’s this idea of the architect expert—it’s a particular kind of character that’s out there, like Howard Roark in [Ayn Rand’s 1943 novel] The Fountainhead, you know? He’s straight, he’s white, he’s a man, and he builds—erects, as they say. People may laugh about that stereotype but I don’t think we’ve moved that far away from it.

So a lot of Black women who trained as architects end up doing something else. I trained as an architect, but I’m not licensed—I work on various aspects of the built environment, but through writing history, curatorial projects, art projects, design projects. If I’m going to work on issues of Blackness or anti-Blackness, architecture is too limited and I need to be more expansive with ideas, references, and resources.

LHYeah. Out here we have the LA Black Worker Center, which basically unionizes folks to place them in the construction field, and then holds accountable these industries that are developing and claiming “diversity” or whatever but not hiring us. I wonder why I don’t see that more in LA, because once you have people who live in the neighborhood building something, I’m not saying that they instantly become designers, but it just becomes a lot more poetic. So that’s something I wish I saw.

MWMany of the building trades have long histories of racism. Certainly in New York City, there were ethnic groups that did certain kinds of work. Unions were a big part of trying to integrate the trades, but sometimes unions reinforced segregation. But I think you’re right, having people who are building locally works. This would be an ideal for a place, because construction workers are paid well—it’s hard work, but it keeps the wealth in the neighborhood.

LHIt’s crazy driving in the neighborhood and it’s like, Well, this isn’t for us, you know? In West LA there’s the Cumulus project—for a year now, two years, we’ve seen them building up this fantastic building, and the results will be extreme displacement. You go online and look at the floor plans, and they have a two-bedroom penthouse for $16,000 a month. It’s a total separation from the community in every aspect. But I hope one day I can land on some space and build with people here, developing our own spaces as a community-land-trust effort.

MWThat’s the problem of the real estate industry and development: it’s all about extracting money. Sometimes I feel like a building is just the residue of some financial transaction by some offshore legal entity, moving money through the building to go who knows where and to whom. Rather than the building being the focus, built well and made meaningful because it’s going to be here longer than any of us, it’s just a financial instrument for making money. The conditions of who’s going to live there or work there are kind of afterthoughts, right?

LHTotally. And even the workforce.

MWExactly. But even before Blacks in this country could enter the architecture profession, there was a whole history of Black builders. That’s what people were doing to build. And because it wasn’t formal architecture, with drawings filed with the building department and so on, the archive doesn’t really tell us much about those buildings or who built them. So we need to develop a whole other way in which people research these Black histories.

LHTotally. Before LA was going through this phase, I’d see all these empty lots down main boulevards here and just sort of dream up these spaces that I wanted to see. Now, if I started building off the strength of just doing it, oh God, they would shut me down in five seconds. So the goal is to somehow acquire the land, and then try to exercise the community-land-trust model, like other mission-aligned, value-aligned folks, to just get to building our own spaces together, you know? To build our own architectures, our own gardens, our own spaces for leisure—I can’t even fathom what that would be like because I’ve always lived in other people’s spaces that don’t reflect me, you know?

MWYeah. But look at Simon Rodia and Watts Towers.

LHTotally. But do you think that could happen in 2021?

MWI don’t know. Rodia just did it. And then the city tried but failed to tear the towers down—

LHAnd now it’s a landmark.

MWYeah, now it’s a landmark. Rodia believed, I have this vision and I have to build it. And he did. The Watts Towers have inspired so many after him. So I do think it’s possible.

Social Works: Curated by Antwaun Sargent, Gagosien, 555 West 24th Street, New York, June 24–August 13, 2021

The “Social Works” supplement also includes: “Notes on Social Works” by Antwaun Sargent; “The Archives of Frankie Knuckles: Organized by Theaster Gates”; “Carrie Mae Weems and Maya Phillips”; “Sir David Adjaye OBE”; “Allana Clarke and Zalika Azim”; “Rick Lowe and Walter Hood”; and “Linda Goode Bryant and DeVonn Francis”