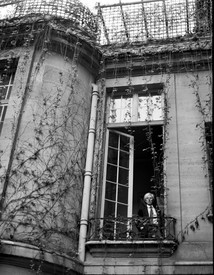

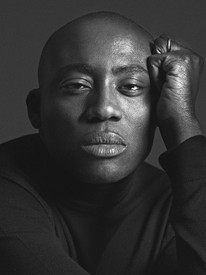

William Forsythe has been a radical innovator in choreography and dance for more than forty years. In redefining the very syntax and praxis of his field in groundbreaking choreographies for professional dancers, he has also created installations, film works, and interactive sculpture. In the fall of 2017 Forsythe had his first gallery exhibition at Gagosien Le Bourget.

Louise Neri has been a director at Gagosien since 2006, working with artists and developing exhibitions, editorial projects, and communications across the global platform. A former editor of Parkett magazine, she has authored and edited many books and articles on contemporary art. Beyond the exhibitions she has organized for Gagosien, she cocurated the 1997 Whitney Biennial and the 1998 São Paulo Bienal, among numerous international projects.

At a time when the art world is embracing choreography in all its forms, this fall Gagosien will present William Forsythe’s compelling Choreographic Objects at Le Bourget.

Forsythe is a radical innovator in choreography and dance, revered the world over. In a career spanning more than four decades, he has produced an extensive repertoire of groundbreaking ballet choreographies and experimental, non-proscenium-based dance-theater works, as well as an open-access digital platform for dance analysis, notation, and improvisation. In the process, he has redefined the very syntax and praxis of his field, and exerted unparalleled influence on subsequent generations of artists.

In tandem with the evolution of his choreographic performances, Forsythe has been working for more than twenty years on installations, film works, and discrete, interactive sculptures that he calls “choreographic objects.” Consistent with his expanded conceptual aim of activating ordinary observers to choreograph themselves, the Choreographic Objects prompt the conscious engagement of humans in a given environment. Here, Forsythe discusses them with Gagosien director Louise Neri, a longtime friend and collaborator.

Louise Neri What was the impetus for the Choreographic Objects?

William Forsythe It all began in 1990 with an invitation from the architect Daniel Libeskind to participate in his permanent municipal installation project The Books of Groningen (1991) in the Netherlands. His proposal was based on his belief that his métier might not be entirely dependent on practice-related expertise to achieve its goals, that it could be a robust platform for trans-disciplinary artistic discourse. My participation enabled me to see how the mechanics of choreographic strategy could be demonstrated effectively in adjacent domains and other media besides the body.

LNCan you describe your aims with the Choreographic Objects?

WFIn the twenty-six years since The Books of Groningen, this unique discursive relocation has supported a wide range of choreographic models, from the immense White Bouncy Castle (1997) to a suspended timber shed that responds to the forces that one’s body exerts on it [Underall, 2017] to a feather duster that resists all attempts by the hand to still it [Towards the Diagnostic Gaze, 2013]. No matter how diverse the scale and nature of these projects have been, they all strive to give viewers an unadorned sense of their own physical self-image and to return the analysis of kinetic phenomena that was previously the exclusive purview of professionals to a platform that speaks clearly to the nonspecialist. So the Choreographic Objects are, essentially, modeled abstractions.

LNCan you explain how you “model” them?

WFThe actual modeling frequently uses patterning structures like counterpoint to achieve its goals. The faculty that allows us to unconsciously negotiate with life’s aleatoric distribution of patterns is key to one’s well-being; works that are contrapuntally structured are, in a sense, exercises for that faculty which accounts for a significant part of one’s survival.

LNWhat are you exhibiting in Paris?

WFAt Gagosien Le Bourget I will present Black Flags (2014), an imposing visual spectacle; Towards the Diagnostic Gaze; and the video sculpture Alignigung (2016), a composition with two dancers. Then, later in the fall, La Villette/Grande Halle will present a version of Nowhere and Everywhere at the Same Time (2013), a vast field of pendulums that viewers may enter.

LNIn preparation for our discussion, I read a reflection by Karl Popper on Julien Offray de La Mettrie’s L’Homme machine (1748) where Popper concludes that there might be no clear distinction between living matter and dead matter and that man may indeed be a computer.1 Given your engagement with robotic technology, is either philosopher of interest to your own work?

WFIn contemporary terms, La Mettrie’s eighteenth-century treatise translates to a computational theory of mind. As humans we constantly deploy a faculty that, in all levels of interaction, conscious and unconscious, participates in a predictive, statistically calculated engagement with the environment. You use this faculty to determine how much salt goes in the soup; when pouring milk, you figure out the speed at which milk’s flowing out and you adjust the tilt of your hand and arm unconsciously to stem or increase the flow; putting your socks on while standing on one leg, trying to park your car—these “calculations” based on accumulated experience are going on all the time.

LNIn some areas of industrial design, humans are considered to be more perfect machines because we possess greater tactile capacities for nuance and anomaly. For example, the extreme curves of surfboards can’t be preprogrammed in assembly-line manufacture, they must be made by hand.

Within the general framework of the Choreographic Objects, Black Flags is really the first of them in which you promote a literal idea of surrogacy, a process of transferral by which mechanical creatures are activated so as to appear to be alive, interacting in complex relation. It’s also the most powerful analogy you have made in this body of work to choreographic interaction. This work poses many ontological and philosophical questions.

As humans we constantly deploy a faculty that, in all levels of interaction, conscious and unconscious, participates in a predictive, statistically calculated engagement with the environment.

William Forsythe

WFThe word “surrogacy” is very apt. To some extent, most of the Choreographic Objects serve as surrogates for real-life interactions with the human environment—stepping off the curb, running to catch a bus, avoiding a swinging door, and so on. All of the objects simply isolate coordinational transactions that abound in one’s normal everyday environment—not tipping a chair, avoiding stubbing one’s toe, and so on. What I frequently attempt to do is isolate phenomena that are so fully integrated into our unconscious physical selves they’re invisible to us.

LNCan you give concrete examples?

WFTowards the Diagnostic Gaze renders the body’s pulses and tremors visible through the fibers of an ordinary feather duster. In the case of Black Flags, the phenomenon of contrapuntal patterning is, for me, a natural thing. It occurs visually and acoustically all the time. If one subscribes to John Cage’s idea that music is a ubiquitous phenomenon and does not emanate exclusively from controlled sources, then we can imagine it as a pointillist, contrapuntal web or veil of phenomena that is constantly exerting itself on our senses.

LNHow did you come to imagine using industrial robots for your work?

WFI am fascinated by demonstrations where flags are used to express social or political unification or solidarity—in civic ceremonies, sports, political rallies. For Black Flags I used the same scale of flag that crops up in football games. In that context the flags are powered by humans, which is very difficult to do. It’s obvious that whoever wields them is dedicating his entire body to the task in a very specific way. It’s a challenge that almost can’t be met. I was fascinated by this and sought to employ the idea differently.

The initial impulse of Black Flags was calligraphic, inspired in part by my earlier dance work for Ballett Frankfurt As a Garden in This Setting (1992), in which David Kern maneuvered a length of light-blue satin ribbon attached to a fly-fishing pole to perform a 3D calligraphic choreography onstage. I thought that I could simply use a motion-capture of his demo and map it onto a program for the robots. But I discovered that it didn’t translate, it was way too complex. I had to take into account the fact that the flags have to slow down at some point; they could not be sustained in a state of constant propulsion.

LNKern was a lone performer; why did you use two robots for Black Flags?

WFThe subject of the work is contrapuntal inscription and the robots together produce a very specific kind of relationship that embodies what’s fundamental and compelling about the properties of counterpoint.

LNDo you describe Black Flags as a duet?

WFI would say more of a two-handed piano composition.

LNDo you find that machines can map contrapuntal relationships more perfectly than humans?

WFPerfection isn’t my foremost concern here. Going back to the football fans, given the scale of the exercise, the sheer demands of force that the imagination of the choreography requires, with that material on that scale and in that space, is humanly impossible. So with the robots I am providing an augmented human practice.

LNDid you at any time consider the early proto-modernist performing artist Loie Fuller, who used the air around her and armatures concealed in her voluminous silken robes to extend her physical presence, appearing onstage as an almost abstract, nonhuman entity? She’s said to have inspired flag-dancing in modern club culture.

WFFuller was prescient in offering a proto-digital kind of abstract visual phenomenon using prosthetic armatures. Conversely, the robots are purely digitally driven entities that bring the body back to mind.

LNThe KUKA robots that you employ have become fairly commonplace in industry. Why did you select these particular models?

WFThey’re possessed of an extraordinary elegance and fit our requirements. The base weighs eight tonnes to counter the kinetic forces. Extending their reach from five meters to thirteen meters with the introduction of flagpoles is a significant accumulation of complex shear forces. These robots possess seven rotating joints, meaning seven degrees of freedom, which offers a planar complexity that for my practical purposes is inexhaustible.

LNIs their planar complexity greater than that of the human arm?

WFMuch greater! Our hands are extraordinary in the way they turn, but imagine if your wrist could move 360 degrees, as well as your elbow, your shoulder, and your waist; and at the same time you could turn around yourself: the counter-torquing, spiraling products of the robotic faculty are really quite mesmerizing.

LNGiven that your dance aesthetic is characterized by extremity with regard to the physical capacities of the dancing body—torque, extension, elongation, and so on—it seems somewhat paradoxical that the apotheosis of your theories is a machine!

WF[Laughs] Especially given that much of the theory that produced these kinds of movements maintains that if we approached ballet as a program, what would the results be? The dancers collaborated as researchers with regard to the proposals I gave them, and the results were their individual solutions to these particular proposals. So I suppose you could characterize our research exchanges as the “if/then” algorithmic type, which is a common characteristic of programming environments.

LNWorking with robots would seem to be a natural evolution of your earlier engagement with neuroscientific research, for example the Max Planck Institutes’ neurological mapping of the dancers in your choreography, One Flat Thing, reproduced (2000). Your work has always suggested a highly technical science, but with improbable outcomes.

WFWhat I’m doing in both instances is choreographing your attention. One Flat Thing, reproduced initially shows you how to read its geometries; the flags show you how to read their contrapuntal relation. The timing of the actions is so constructed as to engage your predictive faculties; for example, if you’re observing a choreographic situation, you might realize that there’s a certain amount of controlled information coming out of it, whether dense or sparse, recognizably patterned or stochastic.What I strive to provide are contrasting structural alternations that play with your anticipation of these informational densities. Juxtaposing these different states is what I consider to be the fundamentals of counterpoint, beginning with irregular irregularity.

LNHuh?

WFIrregular as opposed to regular irregularity which implies an irregularly structured event ad infinitum. For example, if I were to provide an event that’s offering the viewer consistently sustained complex information, at a certain point his or her attention will diminish in order to save cognitive energy, like a screen saver. But then, at some further point, I will intentionally make a structural exception, an interruption of this potentially endless process. The viewer parses this exception as either “anomaly” or “trend.” As the composition’s trends and anomalous tendencies accumulate, the proportion and type of these changes establish an ur-narrative: a product of the curiosity that our interest in predicting pattern produces.

LNCan you give a specific example?

WFFor example, the robots project a sense of threat so one instinctively engages in the outcomes of that affect. It’s like confronting Richard Serra’s Band (2006), or Michael Heizer’s Levitated Mass (2012) at LACMA, where one is prompted to consider the immediate consequences of natural phenomena, including seismic activity.

LNExcept that with Black Flags it’s rather a confrontation with force and velocity, not mass and weight.

WFWith Black Flags the precarity emanates from within the perceived possibilities of the machine, but there’s no mind to the machine and it remains completely at our disposal. That’s not to say that to attempt to interact with the robots isn’t actually dangerous. Once programmed by us, the robots will thoughtlessly execute their full program whether or not a human is in their path.

LNWhen I look at the immense beauty and lethal grace of Black Flags, I reflect on the fact that these very same robots replace humans every day on assembly lines all over the world—Popper’s “living matter and dead matter.” Can you discuss the implications?

With “Black Flags” the precarity emanates from within the perceived possibilities of the machine, but there’s no mind to the machine and it remains completely at our disposal.

William Forsythe

WFI can’t produce a teleology for this particular shift in our civilization, but as humans we have long been fascinated with animation in all its forms, from the earliest automatons of ancient Greece and China to the most recent developments in animatronic illusion, as in Walt Disney’s Pandora-world-of-Avatar, which represents the acme of dissimulation. My choreography of the robots is not at the service of direct theatrical affect. Rather, I am trying to engage with abstract values, modeling complex surfaces into volumes. The single element that these particular objects share with humans, and that is essential to their respective functioning, is air.

To return to Loie Fuller, what contributed to the abstract sophistication of her art was her proprioceptive ability to anticipate the aerodynamic effects of her accelerations on her material. On the other hand, with the robots, the physical consequences of all the interactions of material and air had to be individually and meticulously programmed. While conceding that the robots emulate certain human attributes, I also tried to deanthropomorphize their interactions so that they would be perceived more as pure compositional entities. I’m striving to make a formal statement in the way that music hangs in the air.

LNSo could you also call this a formal exercise in recontextualization?

WFIndeed. When Duchamp removed the readymade from its daily use, he assigned it another purpose, that of being for aesthetic contemplation. I have removed the robots from their frame of capital and transformed them into compositional instruments, like a piano. A piano is not useful for anything other than making music, but industrial robots can also be employed to “make” choreography. In the gallery they become sublime objects, but when I stop using them, they go back to the factory, lapsing back into industrial obscurity.

LNA recent New York Times image of a KUKA robot in a cage in a Chinese solar-panel factory really stuck in my mind, but to infer that they’re trapped there would be a little too emotive. You have created a sense, or an illusion, of setting them loose.

WFI have assigned them a poetic task.

LNIs that challenging in terms of programming?

WFYes, given the safety parameters that are built into the robots to protect humans. When we were programming, the robots often overrode our will if we wanted to move too rashly or with more force, because they’re also programmed to protect us from their force when they approach the observational perimeter.

LNPrecariousness—disequilibrium, asymmetry, counterpoint—is always a key element in your distinctive choreographic language. It also pervades the Choreographic Objects, as expressed in the precariousness of the image itself, as in Additive Inverse (2007), or in the danger of proximity that Black Flags imparts to the environment it shares with us.

WFMany of the Choreographic Objects have to do with acknowledging mortality. Our bodies are precisely not machines; they’re fragile, subject to ebbs and flows. The world does not come at us in evenly measured portions but in a contrapuntal cloud. Our predictive faculty exists for our own self-preservation, and through evolution we became capable of recognizing precariousness and deriving as much information from it as possible so that our relationship with the world developed heuristically. In a certain sense, the Choreographic Objects provide us with cues for our future levels of self-knowledge—what we need to recognize. For example, if you’re trembling way too much with the feather duster of Towards the Diagnostic Gaze, you need to consider whether you specifically might need clinical help or whether your behavior is generally reflective of the human condition.The Choreographic Objects are diagnostic equations that ask: How am I in the world as a body? It’s evident that we’re not robots.

1Karl Popper, “Of Clouds and Clocks,” in Popper, Objective Knowledge: An Evolutionary Approach, 1972 (rev. ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 1979), p. 224.

Artwork © William Forsythe