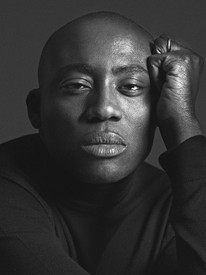

Fiona Duncan is a Canadian-American author and organizer and the founder of the social literary practice Hard to Read. Duncan’s debut novel, Exquisite Mariposa (Soft Skull Press), won a 2020 Lambda Award. She is currently developing a narrative biography and critical study of the transdisciplinary American artist Pippa Garner.

Mindy Seu is a New York–based designer and technologist, an assistant professor at Rutgers University’s Mason Gross School of the Arts, and critic at the Yale School of Art. Her expanded practice involves archival projects, techno-critical writing, performative lectures, design commissions, and close collaborations.

Tiziana Terranova is an Italian theorist and activist who studies the effects of information technology on society and explores concepts such as digital labor and commons. Terranova has published the monograph Network Culture (Pluto Press, 2004).

The Internet and digital technologies, from smartphones to social media, have transformed everyday life for their users, mapping and multiplying the connections one makes, be they jokes or financial transactions. Communication and capitalism have accelerated. Surveillance has become a given; data is the new currency. These changes have been so epic and so swift, normalized but not yet naturalized, and often creepily imperceptible (how apps can manipulate the human nervous system, for example), that it’s been difficult to keep up with what is actually happening on a structural level, especially when an estimated 5 billion people worldwide are online to distract and overwhelm. As one viral tweet put it, “We was not supposed to know this many people existed, let alone they thoughts” (Twitter handle: @ethnyagami).

Two people whose thoughts you might actually want to know about, professors Tiziana Terranova and Mindy Seu, have each just published books on the recent history of the Internet. Terranova’s After the Internet: Digital Networks between Capital and the Common, part of Semiotext(e)’s Intervention series, collects dispatches from her firsthand research on the emerging technologies and techno-economies that have defined the last decade, including the attention economy and its psychopathologies. Complementing Terranova’s slim volume is Seu’s cake of a book Cyberfeminism Index, an “anticanon” encyclopedialike collation of more than 700 diverse international manifestations of cyberfeminist activism, art, community, engineering, and scholarship. Drawn from a website of the same name (originally commissioned by Rhizome), Cyberfeminism Index in book form becomes an art object: wrapped in “chroma key” green-screen green, it re-creates the rhizomatic web of its subject matter through extensive cross-references.

In an effort to better understand the recent past, present, and future of the Internet, we brought Terranova and Seu together to discuss their practices and their latest publishing projects.

—Fiona Duncan

Fiona DuncanIf you could introduce yourselves and your practices in your own words, I’d love to hear how your work extends beyond writing and publishing.

Tiziana TerranovaI’m a full-time professor at the Università di Napoli L’Orientale. My practice there is typical of a full-time academic—research and teaching—but for many years I have also been an active member of Uninomade and Euronomade, which are “free universities” that have aimed to produce and disseminate politicized knowledge for social grassroots movements such as those running “occupied” spaces in Italy and elsewhere. They call these “liberated” spaces run as commons.

Mindy SeuI’m an assistant professor at Rutgers University and I teach in the MFA Department at the Yale School of Art. My practice is also grassroots centered. I focus primarily on the activation of digital archives, specifically those that are community created. This expands into digital technologies at large, such as smaller Internet cultures, revisionist histories of the Internet, and considering how to surface those for new readerships while paying respect to the people who have pushed forward those communities from the start.

FDBoth of your books collect existing writings and documents from a specific period of time. Both end with the same year, 2020. Could you talk about the bracket of time that you chose?

MSThe Cyberfeminism Index begins in 1991 because that was the year the term “cyberfeminism” was coined simultaneously by two different groups, the Australian art collective VNS Matrix and the British cultural theorist Sadie Plant, each unbeknownst to the other. Cyberfeminism emerged as a provocation to ask women and marginalized communities how they might shape cyberspace in opposition to the stories told by the hard sci-fi of the 1970s and ’80s. The book ends in 2020 but the online archive from which its contents are drawn, cyberfeminismindex.com, will grow in perpetuity. It’s still open source, open access, and continuing to be crowdsourced.

TTI read the Cyberfeminism Index. It was exciting. I was in the UK during the 1990s and early 2000s and would travel to Warwick University to see the events that Sadie Plant organized. It was a really exciting time. My book for Semiotext(e) comes after that—it belongs more to the 2010s, after I had moved back to Italy. It’s a collection of essays I wrote while active with Uninomade and Euronomade’s free informal networks of scholars and activists working in the wake of the Italian postworkerist tradition. Most of the essays in After the Internet were written in the 2010s, when the cyber utopia of the 1990s and 2000s was being captured and reprogrammed by platform capitalism.

FDIn your incredible introductory essay, Tiziana, you help clarify what we’ve been experiencing with regards to the Internet, social media, and digital technologies over the past decade, calling the 2010s “the accelerationist decade,” for example, and introducing the ominous term “corporate platform complex (CPC).” Could you explain what you mean by CPC?

TTIf you look at the way the topology of the Internet has changed, there is this myth, taken from Paul Baran in 1964, that the Internet is a mesh network where every point can connect to any other point. That was part of the utopia of the 1990s. In reality, the Internet was always more of a decentralized network, there was always a backbone and centers that were more powerful. But that is still different from what we have today. The topology of digital networks has changed. What we have are a few content and service providers, endowed with large server farms, that describe themselves as “platforms.” You go from platform to platform, from Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok to WhatsApp, YouTube, Google, and then maybe you have Telegram or Signal. Most people relate to platforms. In the introduction I say that the Internet is dead, but only in the sense that it’s become residual—it operates in the background but it no longer signifies for most people the possibility of a different, better world.

FDI love when you call the Internet “not so much dead as undead.” A zombie Internet.

TTBecause these platforms have constructed something different. From a certain point of view, the Cyberfeminism Index documents all that has been pushed to the sidelines, which is not to reduce its importance.

MSIt seems like you’re describing this infrastructural shift from Web 1.0 to Web 2.0. Now, with Web3, this evangelism around the commons or cooperatives is emerging again.

TTWhat do you think about it? Is there a cyberfeminist kind of blockchain?

MSAbsolutely. The focus of Web3 has been on decentralized protocols, from blockchain to p2p, seemingly pseudonymous yet mapped onto an open ledger. Early adopters of new technologies have always been cyberfeminists, and specifically sex workers, because their work is so criminalized, forcing them to find the new cutting edge. Sex workers were some of the first people to use cryptocurrencies, since traditional payment processors considered those that did not abide by their morality clause “high risk.” They have chains that use great puns like “titcoin” instead of bitcoin. I do see some of the potential of the Web3 space. I think what confuses me are these claims of decentralization. It feels centralized, since many NFTs are circulating through the same platform, OpenSea, and most transactions are happening on the same handful of chains. It also doesn’t feel as ubiquitous and open access as its evangelists’ claims are because it requires such tech literacy to onboard people. It’s like someone telling you this is the future but not letting you know how to join them.

We need a language of being with machines that is not the language of using and being used, mastering or serving. That also implies a liberation of machines from our racialized and gendered projections of our fears and desires.

Tiziana Terranova

TTThe book I’m working on at the moment, which I started after finishing most of the essays in After the Internet, is called Network Social. The idea started with this return to the social (social web, social media, then social computing, computational social sciences, etc.) in the early 2010s. With relation to the “network social” (which is neither network society nor social network, as I explain in the book), I was immediately fascinated by the ways in which the blockchain was at least at the beginning deliberately antisocial. It was the idea that you could do without the social component of communication, a reaction against the hegemony of social media.

MSIt seems like a retaliation is happening against these platform oligopolies and their viewership model. Venkatesh Rao writes about “the domestic cozy,” Gen Z–focused online social happenings for a very small group, rather than the late–Web 2.0 desire to have as many followers and viral hits as possible. In some ways, this kind of privatized, smaller social group allows for more of this online intimacy to happen.

FDAlready in our talk we’ve pointed to how your practices and books complement one another: After the Internet references diffuse countermovements and resistances that the Cyberfeminism Index thoroughly documents, while the Cyberfeminism Index references the power structures that After the Internet reports on. One way to contrast each book’s scope is as mainstream and countermainstream. There’s also a gendered element: feminisms contra the predominantly white-male ownership of big tech. I was also thinking of scattered power versus consolidated power.

MSIt’s tricky. While the framing always seemed to describe a primary or hegemonic class and then the people on its outskirts, some groups in the Cyberfeminism Index did not want to be positioned as other or in the margins. Many groups tried to develop their own infrastructures, refocusing the parameters of these spaces and who is at the center. It’s interesting to think about the different forms of cyberfeminism that have emerged in different regions. What was happening in Australia, Europe, and the US is different from what was happening in East Asia, Latin America, and South Africa. Cyberfeminism continues to feel like this very rhizomatic web where different manifestations have complementary themes even if they didn’t come from the same root. In that way, if you imagine it as a net, it does actually feel very decentralized.

FDWhich is echoed in the construction of your book. Could you describe the formatting of the Cyberfeminism Index in print and how it mimics this rhizomatic web?

MSThe format was inspired by a lot of things, namely The New Woman’s Survival Catalog [1973], which was billed as the feminist Whole Earth Catalog [1968] of the 1970s, as well Lucy Lippard’s Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972 [1973]. Rather than an essay anthology, Lippard’s book is an annotated chronology of excerpts from different writings about the dematerialization of art. That felt like a good lens for how to structure the Cyberfeminism Index, which acts as a sourcebook or encyclopedia, something that you pick up, open, and intuitively select. You have your primary index, an annotated chronology. You have an index of titles, people, and images, and then each entry has cross-references that push and pull you to different entries with complementary or juxtaposed themes. The design also leant on early examples of analogue hyperlinks. Hyperlinks emerged as cross-references, footnotes, and bibliographies in printed volumes long before we had them on the Internet.

FDExploring the book made me conscious about how I read books in print and how I use or am used by the Internet. A hyperlink in print is much clunkier than online, with the efficacy of clicks. I wanted to talk about use and users. I’ve heard Mindy speak about web “users” being “a contentious term.” I’m also thinking about this quote from After the Internet: “The ‘user as master of the machine’ has waned but what has waxed in its place is also not quite reassuring. The consensus seems to be that the user has morphed from master to addict.” I don’t even know where the term “user” comes from in a computing context.

TTIn A Prehistory of the Cloud [2015], Tung-Hui Hu describes it as “a product of the invention of time-sharing, which initially occupies a ‘peeping’ and intimate position with relation to the machine,” but it was with personal computing that the user came to be refashioned in ways that mapped the identity of the user onto the time she or he spent on the machine. In Wendy Chun’s genealogy of software, there is also a very gendered history of programming at work: 1990s hacker groups were all about mastery of the machine. You had the hacker figure, the heroic figure, the programmer, the masterful subject, which was mostly coded as male. The racialized language of user as master, and of man and machine as master and slave, has been problematized by recent work on the intersection between race and technology—from Louis Chude-Sokei to Neda Atanasoski and Kalindi Vora to Denise Ferreira da Silva’s brilliant critique of the TV series Black Mirror. In the 1950s, the French philosopher of technology Gilbert Simondon argued that the master/slave model of the human relation to the machine was established during the industrial mode of production; we’re more aware of it now in terms of its derivation from the plantation economy. In the industrial factory, the machine was below or above, you were either the overseer or the slave. What does it mean to have instead a sympoietic relationship with machines, as Donna Haraway has argued for organic critters? We need a language of being with machines that is not the language of using and being used, mastering or serving. That also implies a liberation of machines from our racialized and gendered projections of our fears and desires.

FDWith the term “user” I also think of drug use and addiction. Being addicted to one’s phone is something I hear people bemoaning all the time now. It’s interesting that it’s the phone. “I’m totally addicted to my phone,” not—

MSThe software.

FDExactly. After the Internet tackles the attention economy and Internet addiction. Tiziana, could you speak to that?

TTAs the Internet became a mass thing, you got this exponential usage. New kinds of interfaces were developed that aim to maximize engagement. They follow design principles recalling those studied by anthropologist Natasha Dow Schüll in her book Addiction by Design: Machine Gambling in Las Vegas, which shows how the design of betting machines changed so people aren’t in the social space of a casino any longer, they’re just spending time and money on machines. They don’t even want to win anymore—they just want to lose all feelings of mastery, to divest themselves of power, almost. That happened with the Internet as well. The attention economy surfaced. We were no longer in the 1990s and early-2000s world of unlimited abundance, where the idea was that everything was free and could be freely shared. For mainstream economics, there is no economy without scarce resources—the economy is the allocation of scarce resources for alternative ends. Only once there was something that could be scarce—users’ attention—could there be an economy. I noticed how neuroeconomics describes pleasure as the necessary mechanism that makes an economic subject; you need to be able to strive for a reward. One of the essays in After the Internet is something I wrote for the “Psychopathologies of Cognitive Capitalism” conference series organized by the artist Warren Neidich. I use a neuroscientist’s experiment on anhedonia, the incapacity to feel pleasure. Anhedonia became a pathology to be very concerned with, because you have to be able to feel pleasure to be an economic subject; you have to pursue pleasure, you have to pursue rewards. If you reject them you’re pathologized.

FDThis actually reminds me of one of the illustrated entries in the Cyberfeminism Index, Shu Lea Cheang’s science fiction porn film I.K.U. [2001].

MSI.K.U. is an amazing example of soft science fiction that begins where Blade Runner [1982] left off. In this dystopian techno future, Cheang illustrates a new economy built around I.K.U. coders who extract orgasm data rather than using money.

TTYou know, I started by writing SF, then ended up writing mostly academic essays. My BA, MA, and PhD theses were all about SF: Joanna Russ, Philip K. Dick, and cyberpunk. After the Internet ends with a short SF story about a fugitive AI, too.

MSI’ve also been drawn to science fiction and you see a lot of that throughout this book. The root of the word “fiction” is actually the Latin for “to form.” It’s easy to see why these narratives and science fictions end up shaping future infrastructures. They change the cultural consciousness of what technology is able to do.

FDFrom the zombie Internet to sci-fi—I love how we are getting into narrative here. Could we also think about Greek tragedy? It seems like we are witnessing a hubristic rise and fall with some of these megalomaniac tech figures. Can narrative precedents give us any clues into what the future of the Internet might be?

TTI think that Yuk Hui has a point when he says that we need to recognize how much myth there is in our philosophy as well as in our relation to technology—Prometheus or Icarus, for example, in Greek mythology. Maybe we should explore other mythological stories about technology (Hui starts with a Chinese story where there is no hubris but a relation to the elemental forces of the cosmos), or make up new ones. Cyberfeminism and Afrofuturism would be good places to start.