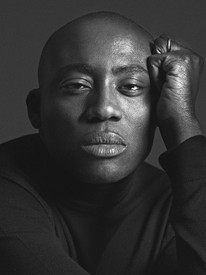

Hans Ulrich Obrist is artistic director of the Serpentine Galleries, London. He was previously the curator of the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. Since his first show, World Soup (The Kitchen Show), in 1991, he has curated more than 300 exhibitions. Photo: Tyler Mitchell

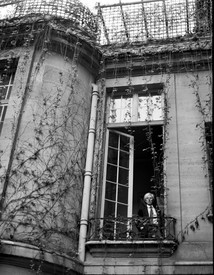

Rudolf Polanszky is an artist who lives and works in Vienna, producing painting and sculpture using a variety of materials. His works have most recently been exhibited at the Secession, Vienna; 21er Haus, Vienna; Rubell Museum, Miami; and the Bunker, West Palm Beach, Florida. They are held in the permanent collections of the Centre Pompidou, Paris; Artothek des Bundes, Vienna; and others.

Hans Ulrich Obrist Rudolf, how long have you had this studio in the country?

Rudolf Polanszky This ruin? Since 1979, but I never used it much in the past. Back then, it was just land on a dead-end street; there was nothing. But the location was so convenient, an easy half hour from Vienna.

HUO And before you were working out here, your studios were always in Vienna, right?

RP Yes, but those too were always somewhat morbid structures of decay. I have a type, apparently. I had a huge basement studio—450 square meters—beneath a restaurant in Schlösselgasse. It was spacious, enough to parcel out two defined spaces there. I eventually shared the space with Franz West. We were working there for a while until they threw us out and turned it into a swingers’ club—not a bad solution.

HUO This was in the 1970s?

RP That was in the late ’70s, early ’80s.

HUO To go back in time a bit, at what age did you first realize that you were interested in art?

RP Well, that’s an interesting question. I wonder about this myself. My father was a jazz musician and my mother was something of a designer. They were always abroad. We were never stationary, never native, so to speak; we were always alienated, in a sense. On the one hand, that was very good; on the other hand, always having to get used to different people presents a problem, for young people especially. When I became independent, I returned to Vienna and settled down in a way that I never had before. It was then that I got to know people who were interested in literature, philosophy, and art. Of those, the concept of art struck me as the most difficult and therefore the most engaging.

One of the main ideas back then was about art’s inability to be defined. Anyone can claim that something is art; no one wanted to define it, or at least people were saying that it couldn’t be defined. So I said, Why not? I thought about it for a long time and realized that art and the questions surrounding it are the only way for me to think clearly. Art seemed to be the only way of proceeding with a maximum of what I felt so robbed of, namely, the idea of freedom. There are no parameters for good and bad, true and untrue—all these limiting elements in life. In art there were different questions, procedural ones: What can I do? How can I decide how to do it?

Of course, I must be clear in speaking to you that I’m using the concept of freedom in a limited sense. The way we are made, what we can do and believe—there are real limits. Freedom is a chimera in a sense, but this illusion is realized as far as is possible in art. I can do something, and you can say, “No, don’t do that, that’s wrong,” but I’ll do it anyway.

HUO What year would that be, this epiphany?

RP That must have been in the early ’70s. I started making the Lard Drawings in 1976. Those were the first experiments. The problem I was looking into was, Why do I make an artwork and how do I approach it? Do I make any decisions for doing that, and how do I justify them? And then I thought, I must find concepts that give me a preformation, a method already created, or created in me. When I believe something is self-evident, even though it is not, how do I bypass and turn it off, so to speak? That means not doing anything for purposes of beauty, good, right, or whatever. I’ve been trying to find structures that will make these factors impossible. With the Lard Drawings, for instance, I made them in the dark.

HUO A kind of rule of the game: no light.

RP Exactly—darkness was the control I chose in that case. Consciousness should be limited as much as possible. And they’re drawings, so there are linear structures—that happened immediately—but they were just a kind of ladder to or skeleton of something else.

You go into the fog and feel your way through.

Rudolf Polanszky

HUO Why use fat? Joseph Beuys chose that medium as well.

RP Yes, but he had different methods and different goals. I used fat because it doesn’t bind. That is, if I make a nice stroke on the paper one day, the day after tomorrow it will be completely different. So I can’t really decide how it will be—that was the joke of it.

HUO So the work remains contingent, or built around coincidence.

RP After those works, I began studying physics and quantum mechanics. The language and methods of those fields appealed to me, especially the building of avoidances into the game itself. That idea led to the Coil Spring Pictures, for which I used a coil spring, hopping around with great difficulty and lapses of control. The results were impossible to predict in advance.

HUO The final images were the quasi relics of these processes?

RP Yes, the relics. In using a method like that, I get just the results that emerge among the many possible outcomes of the method.

HUO These action-based practices recall the Aktionismus generation of the ’60s in Vienna, but you felt no relation to activism, unlike West or earlier artists in that lineage. Can I say it like that?

RP You can say it like that. Of course, that background and history were there in my subconscious, but tracing or imitating anything was completely impossible for me. One aspect of all this was the avoidance of adaptation. I always saw adaptation as an abomination.

HUO And then, during this period, you made a series of Super 8 films in which you are the protagonist, the actor, and at the same time the one who realizes the experiment. How did these films come about, and what’s their role in your larger practice?

RP Part of it was that I wanted to see for myself what I was doing. For that the films were useful tools—a kind of “semiology of the senses.” Indeed, that was the title of a series I made in 1976–79. It was predicated on the fact that my drinking colleagues and I were very uninhibited in our drinking. I could see how their physical condition changed as they drank; they would start to fade, their hair stood up—I can recognize a drunk immediately—but I couldn’t see those changes in myself and for myself. So I bought a very bad wine, thinking I couldn’t drink too much of it. That was the wrong choice, because the wine was so bad I fell ill. I set up the camera and then went through the typical processes, all very banal: lift glass, drink, smoke, look to the left of the window, and so on. Then when I was drunk I painted. A semiological pattern emerged through these repetitive colorations; I was seeing an inherent rhythm.

HUO The poet Friederike Mayröcker once said that in one way or another artists always have an addressee. The addressee is often only one person. Who would you say this and other works have been addressed to?

RP The addressee? That’s a good question. I just didn’t look for an addressee—it was always me, you could say. That’s why I later worked with mirrors.

I have a poet friend, Ferdinand Schmatz. He seems to have the real portrait of Dorian Gray at home, he looks like he’s forty—of course you notice things when you get closer. Anyway, we used to meet every day and discuss philosophy, give each other things to read. We were mainly interested in the possibilities that appeared available to us. What’s possible in art? We also read many things skeptical of art: I didn’t become an artist because I had great faith in art’s possibilities, but because the concept of the possible maximization of what we call freedom, by eliminating controls as far as possible, gives me the idea I’m looking for.

HUO In the ’90s you began a series called Reconstructions that continues to this day. Within Reconstructions there are a lot of subcategories, like “Drifting and Sliding Pictures” and “Deformed Symmetries.”

RP Yes, I work differently to summon quasi-random elements. “Drifting,” for example—what does that mean? I smear paint on a canvas, then arrange it symmetrically with materials like plexiglass and aluminum. Then I jump on the plexiglass and slip on this jellylike substance beneath it. This collides with the paint and aluminum. I do this two or three times, one on top of the other, and that’s why the series is called “Drifting and Sliding,” because of these slides during the procedure.

HUO So it doesn’t repeat in the usual sense?

RP Exactly. And that leads somewhere else. This is my hope—that I always get somewhere I can’t find otherwise. Always try to find new ways. An unknown landscape. This is a very poetic affront. I think that’s what often happens, that you go into the fog and feel your way through.

Artwork © Rudolf Polanszky; photos: Ealan Wingate, unless otherwise noted

Rudolf Polanszky, Gagosien, 541 West 24th Street, New York, March 3–April 11, 2020