Genieve Figgis is an artist who lives and works in County Wicklow, Ireland. She received her BA in Fine Art from the Gorey School of Art, Wexford, Ireland, in 2006; BA honors from the National College of Art and Design, Dublin, in 2007; and her MFA from the National College of Art and Design in 2012.

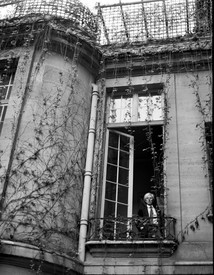

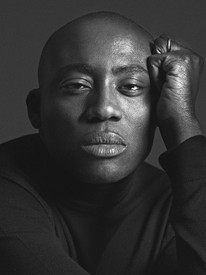

Lydia Millet has written more than a dozen books, most recently the novel Dinosaurs (W. W. Norton, 2022). Her previous novel, A Children’s Bible (2020), was a finalist for the National Book Award in fiction and one of the New York Times Book Review’s “10 Best Books of 2020.” Other titles include the novels Sweet Lamb of Heaven (2017) and Mermaids in Paradise (2015). Millet has been a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in fiction and various other honors, and works as a writer and editor at the Center for Biological Diversity, an organization dedicated to fighting climate change and species extinction. She lives outside Tucson, Arizona. Photo: Nola Millet

Lydia Millet’s Lyrebird is an off-kilter fable that follows a woman’s journey into a new world. As in her National Book Award–finalist novel The Children’s Bible (2020), Millet is a master at summoning a precise atmosphere—a world neither fully realistic nor fully fantastic, but more of a shimmery in-between place that allows for mystery, for the existence of strange animals and unexplained invitations alongside cell phones and car navigation systems.

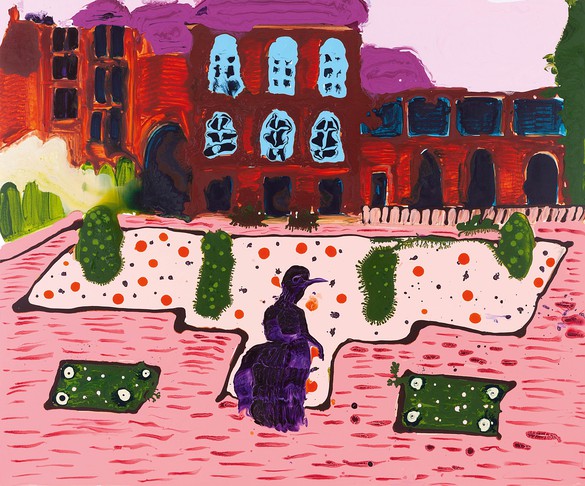

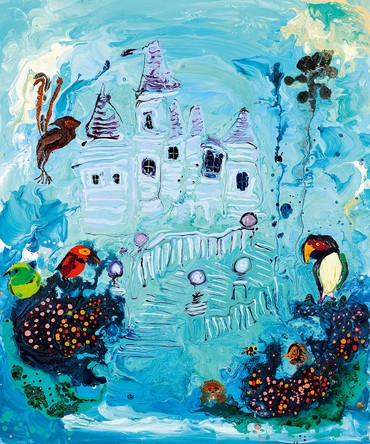

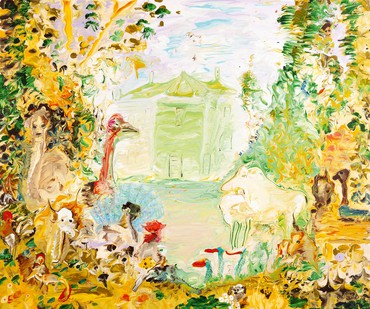

The paintings of the Dublin-born artist Genieve Figgis tweak the inheritance of art history, sometimes playing up the grotesqueries of wealth, other times finding a place for the women lost in classic portraiture. Both Figgis and Millet play with formality, distorting and exaggerating the environments we’ve come to expect. But in neither case is the work caricature; instead, it’s deeply tethered to the natural world, to real life.

Writer and artist speak here about allowing themselves to be surprised by what they find on the page and on the canvas, about the relationship between research and inspiration, and about saying no.

—Emma Cline

Genieve FiggisHow are you doing?

Lydia MilletWell, Thanksgiving is a crazy time for American people. There’s this drive to make a lot of food—it’s very stressful.

GFYes, it’s the same with Christmas here. I do enjoy the decorations and all that, but it’s gotten to be too much hype.

LMThen family is in town, and that brings its own challenges. For example, my brother ordered octopus at a restaurant last night, which, for me, was just brutal. I had to run off to the bathroom to recompose myself, and then I came back and he was like, “What’s wrong, Lyd?” And I said, “Well, I don’t want you to get the octopus.” Which, of course, became this whole thing.

GFThat wouldn’t be my cup of tea either now, Lydia. Because they’re very intelligent, aren’t they—

LMRight, and there isn’t any particularly good way that they’re being raised for food. It’s really bad fishery. But yeah, the octopus—I just can’t deal for some reason. I don’t know.

GFI gave up eating meat when I was about eight. I said, There’s something not right about this. But in my thirties I was working as a chef, and I started to introduce a little bit of chicken here and there—but I wouldn’t be the greatest meat-eater or anything like that.

LMYeah, I’m not some sort of purist, I have no moral high ground on this, I eat sushi, salmon . . . but certain things I just can’t handle. I think I’m getting weaker in my old age.

GFNo, you’re just more aware of your surroundings and the situation we’re in.

LMI hope so. It seems like we both engage with natural environments quite a bit in our work. Let’s talk about the project—

GFThe first thing I have to say, I loved your story.

LMI’m so glad you did. And I love your paintings. I was so excited to see that it was going to be you responding to the story.

GFI was so honored to be asked. I mean, my God, the story—there was so much in it, it was so colorful. I could have made a million paintings in response. It was a style of project that was new to me—are you more used to these kinds of commissions?

LMNot at all, but I have to say that I like to be given an assignment on occasion. Typically I just do what I want. I mean [laughs], that’s sort of why we’re in this line of work, right? So to have someone ask you to do a project that has a certain goal or structure, a set of parameters, can be quite exciting. I’m not a very visual writer, and to some degree I wasn’t in this piece either, but I think I wrote differently because I knew there was going to be this other dimension to it.

GFWell, you certainly gave me a lot of wonderful material to launch from visually. It was so intuitive to pick up all of these elements from the story—the flora, the endangered animals, the settings. It’s such a complete world. How long did it take you to write it?

LMI wrote it in a couple of weeks. There was a pure enthusiasm that drove it forward rather quickly.

GFThat’s amazing.

LMBut from what I understand, you’re incredibly prolific in your painting, right?

GFYes, I suppose I do make quite a lot.

LMDo you paint every day?

GFNo, I’m not painting daily, but I do a lot of research, which is a fairly continual process. Research is what gets me excited about making work. It’s an essential part of my life. And I consider research in a rather broad sense—reading a story like yours or watching a film can be research, too.

One striking thing about Lyrebird is that it opens with a refusal, a “No thanks.” That stuck with me.

LMThe good thing about refusals, or beginning with a negation, is that it’s an automatic creation of suspense. That tension has been created from which narrative can quickly springboard.

GFYes, and I imagine we, in our work and lives, have to be good at saying no. Painting is very solitary, and I imagine that would be your situation too. You’re on your own, creating; it’s very different from getting out there in the world and mixing and being social.

LMI also feel sometimes that making work and putting it into the world is a better conversation than the ones I get to have at parties. I’ve never liked small talk or been comfortable with it. . . . I develop this urge to be a bomb thrower at a party because I get so restless and bored. Maybe it’s better to do that in the privacy of your own home.

GFWhat inspired Lyrebird?

LMI wanted to write a fable. There’s so much rich imagery in that genre, and it allows for all these layers: physical, material, emotional. And then, knowing that, I kept coming back to a work that my uncle made. He was a painter and a graphic artist by trade, and he did this one huge collage that I still have, called The Emperor’s Nightingale, based on that folktale. I grew up with the collage over our dining room table for my whole childhood, so I thought I’d do a version of The Emperor’s Nightingale, a sort of retelling of that fable.

I wanted to ask you, and it’s a tricky subject to approach, but I think it’s a legitimate one: how do you see humor and comedy in your work? In both of our practices, it seems fair to say, there’s real pathos, but it’s accompanied by moments of levity and humor. In what I aim to achieve, they both have to be present for me. I can’t stand to have a work completely devoid of laughter. And I feel like there’s quite a bit of funny inherent in your work, too, in your faces, your palette, all that stuff—and forgive me if I’m not talking about this in the right painterly way because I don’t necessarily have the lexicon [laughs].

GFNo, I agree. Perhaps some of that is unavoidable with the subjects I’m drawn to, but it also relates to my obsession with color. As I work on a painting, there’s the light and the dark going on, from the eternal garden to the darkness of the unknown. It’s just life, really—can it honestly exist without humor erupting out of these contrasts?

LMAbsolutely. But you’re not intentionally setting out to create a humorous image?

GFNo, I’m not setting out to create any particular mood. I paint in a zone that avoids that kind of thinking and control. At most, there’s what could be called an atmosphere that I carry through, but beyond that—

LMOkay, this happens to me when I’m writing, and maybe it doesn’t happen to painters, but I start laughing mid-sentence. Do you ever laugh when you’re painting?

GFWell, I scare the life out of myself sometimes [laughs].

LMReally?

GFOh definitely. I’ll be in the studio and stop to say, What the hell happened here? There are certainly some surprise elements when you’re collaborating with materials; they have their own behaviors sometimes that you wouldn’t anticipate. So yes, I can see how my works, for certain viewers, may look a bit funny and creepy at the same time. But this is never intentional. At most, I’d say that whatever mood I’m in can saturate the work; it seeps in. And definitely who I am, I’d like to think I have a good sense of humor and I suppose the Irish do in general, but there’s light and dark there.

LMI completely agree. And I feel similarly about control, which you mentioned earlier. When I write, the control I have isn’t particularly a conscious or calculated form. I’m not measuring what I do or dispensing anything in a meticulous way.

GFIf I tried to control anything too much, my head would just keep spinning around thinking about all I wanted to include and I wouldn’t get anything done. As artists, we, in a sense, have all the time in the world when we’re working on our own, and I’ve found that trying to overmanage that doesn’t result in much. It’s just working and then it’s luck, really, isn’t it? It’s just sort of fishing around and trying lots of different things—

LMThat’s why I never plan anymore before I write something. There’s no plan. I just start and then, you know, it is what it is when I’m done [laughs].

GFIt’s good to be free, and then you can edit.

LMDefinitely—you have to be a critic at a certain point, but you can’t be a critic at the beginning.

Artwork © Genieve Figgis; photos: Aoife Herrity

Lydia Millet, Lyrebird / Genieve Figgis, Eternal Garden (New York: Picture Books | Gagosien, 2023)