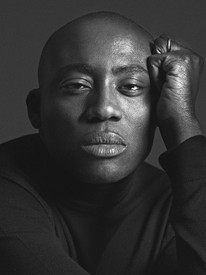

Alison McDonald has been the director of publications at Gagosien since 2002. During her tenure she has worked closely with Larry Gagosien to shape every aspect of the gallery’s extensive publishing program and has personally overseen more than six hundred publications dedicated to the gallery’s artists. In 2020, McDonald was included in the Observer’s Arts Power 50.

Nick Simunovic has led Gagosien’s operations in Asia since 2007. He entered the art world professionally in 2000 with the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation. Simunovic has a BA from Harvard University and an MBA from Harvard Business School.

Alison McDonald What are some elements of the market in Asia that might be surprising to European and American audiences? There are obviously many diverse countries, languages, and affinities there.

Nick SimunovicAsia is an unbelievably diverse place. One of the most satisfying challenges in building our business in Hong Kong has been to learn the different histories of the countries in Asia and their collecting habits. Japan has a three-thousand-year history of cultural production; how do collectors there differ from collectors in China, with its five-thousand-year cultural history but also with a collecting tradition violently upended and interrupted by the events of the twentieth century? Then there are regions in Southeast Asia with their own rich cultural legacies that are coming to the idea of collecting contemporary art for the first time. Or Korea, which also suffered the traumas of the twentieth century, yet collectors there began acquiring serious and sophisticated global contemporary art as early as the 1960s. Many of the most established and comprehensive collections of contemporary art in Asia can be found in Korea—collections with an emphasis on Minimalism, for example, which is typically rare in other Asian countries.

There’s also a sense in Asia that an art collection can serve as an oasis of financial stability in what has sometimes been a turbulent part of the world, for various socioeconomic and political reasons. A collector I work with in Indonesia was one of the first people there to seriously collect modern and contemporary art. While the collection offers him personal joy and a sense of discovery, it also saved his business during the 1997 Asian financial crisis.

Of course, in the past twenty years, China has clearly been the major story in terms of the adoption of contemporary art in Asia. Collectors there are unbelievably ambitious, dynamic, and informed. It’s common for our clients in China to tell me about shows at smaller galleries in New York City, a trend that would have been unthinkable when I first arrived in Asia, almost fourteen years ago. There’s no doubt that over the next hundred years, we’ll see a deepening interest in collecting in China. Collectors there are skewing younger, they’re interested in design, they’re interested in painting and sculpture, they’re interested in installation. They’re incredibly open and they’re receiving vast amounts of information that they process and metabolize very quickly.

AMcDSo many different languages are spoken throughout Asia. Do you ever feel limited in your communication with different collectors? It must be a challenge in certain respects.

NSOf course. But it’s important to remember that we aim to serve all of Asia from our platform in Hong Kong. We’re fortunate that many collectors speak English or have teams that do, and we’ve also built a very talented team throughout the region to work with local collectors in their respective languages. But there are clearly many collectors whom we haven’t met yet and who want to know more about Western artists. We start every day by trying to find and serve them.

AMcDHow does Hong Kong differ from other cities in Asia in terms of the market? What makes it an attractive place to have an art gallery?

NSHong Kong provides many structural advantages that simply don’t exist in other countries in the region. The city is essentially a free port, and the absence of sales tax and import duties has been an enormous boon to the art industry here. Hong Kong is thought of as a hub city, where collectors are comfortable transacting. The common-law system established by the British continues to be in force today. There’s infrastructure to support collectors in the areas of art handling, shipping, logistics, and storage. And between the auction houses, art fairs, and galleries, there’s market momentum.

Finally, Hong Kong is blessed by its location, being geographically situated in the heart of Asia. Half of the world’s population is a five-hour flight from Hong Kong. And while cities like Beijing or Seoul or Tokyo or Bangkok have incredibly vibrant, thriving cultural scenes, the heady cocktail of factors I’ve described above doesn’t exist anywhere else in Asia.

AMcDThe gallery you opened ten years ago in Hong Kong for Gagosien was one of the first international galleries to open there. What was the impetus? Were there signs you were seeing in market activity that showed an appetite for Western artists?

NSI arrived in Asia in August 2007, about three and a half years before we actually opened the Hong Kong gallery. I was immediately surprised at the depth of interest in Gagosien’s program and the number of collectors, even then. Many people were interested in acquiring serious modern and contemporary art from images on my laptop. I tried to get the ball rolling in many different countries at the same time—going to an opening here, meeting a collector there—and slowly we built a business. Frankly, I was astonished at how enthusiastic the response was.

The obvious conclusion was that we needed a gallery in Hong Kong to provide a platform for our artists in the region. Many of our artists—even household names that we take for granted in the West as having monumental influence and impact on the global art world—had never had a gallery or museum exhibition in Asia.

AMcDWas there interest in Western artists? If they’d never shown in Asia, how do you think collectors there knew about their work—what was the channel? And was the knowledge specific to established artists or modern artists, or did it include younger artists as well?

NSIf I think back to our earliest transactions, they happened in places like Taiwan and Korea—countries where collectors had long histories of buying their own cultural patrimony. Some clients might have been buying Impressionist and modern art as a gateway to Western art, but there was clearly curiosity about, and latent demand for, postwar and contemporary art. Many of these clients simply hadn’t met anyone who could offer them a work by Damien Hirst or Richard Prince or Jeff Koons. We were able to crystallize these initial transactions just by virtue of sharing those collectors’ spaces and listening to their interests.

AMcDDo you find that exhibition catalogues or artist monographs are a helpful way of giving collectors more context?

NSYes. Books are invaluable in providing context and credibility—they offer a supportive scaffolding around conversations with collectors. But this phenomenon doesn’t strike me as unique to Asia.

In general, I think collectors here have historically been underserved by Western art galleries. Maybe there were pockets of activity—Japan was of course very busy acquiring Impressionist and modern work in the 1980s and early ’90s—but a willingness to commit to the region and meet collectors on their terms, on their time, and to have conversations about the kinds of artists they find compelling and important? This level of engagement was entirely new. We discovered a huge curiosity in the region for that kind of dialogue and exchange.

AMcDIs it true that you brought the idea of opening a gallery in Hong Kong to Larry Gagosien?

NSWell, I’d been traveling to China with the Guggenheim Museum because they’d organized an exhibition called Art in the USA: 300 Years of Innovation, a survey of American painting and sculpture that traveled from Beijing to Shanghai. I’d had a wonderful experience at the Guggenheim, but I wanted to do something different. Before my work at the Guggenheim I’d been a consultant at McKinsey, so I’d long been interested in business. During my travels to China in 2006, I had a sense that the audience was there but that there were no Western art galleries to serve them. That made absolutely no sense to me and it was clear that opportunity was knocking, however softly. It felt like the right time for me to try something entrepreneurial and Gagosien was at the very top of the list because Larry had the most amazing artists and he’d already expanded to London. I mean, who wouldn’t want to work for the gallery that represents Cy Twombly? Anyway, that was what I wanted to shoot for and I was introduced to Larry through a mutual friend. By that point I’d already decided that I was going to try to make something happen in the contemporary art world in Asia.

Eventually I met with Larry and laid out my rationale. I explained why I thought he should open a space in Asia, and why—even though he didn’t know me—I might be a qualified person to do so [laughs]. At the end of the meeting he starts drumming his desk with his fingers, he looks up at me, and he goes, “I’m tempted. Let’s keep in touch and maybe in a few months we can have another conversation, after you’ve been out there a little while.” Of course I felt somewhat despondent, because I really wanted it to work out. But on the other hand, I felt like I’d put my best foot forward. Anyway, the next day he called me and said, “Let’s do it.”

Hong Kong is the third-largest art Market in the world. . . . We’re still discovering the contours of what’s achievable here, and I find that enormously exciting, challenging, and rewarding.

Nick Simunovic

AMcDThat’s very funny. I’m surprised it took him that long [laughs].

NSFour weeks later I was in Shanghai.

AMcDYou started in Shanghai, not Hong Kong?

NSThe staggering scale of the Chinese economy made it the obvious destination, but 2007 was very early days for Western contemporary art there. Between a punitive tax structure, a small collecting community, and my inability to speak the language, we decided that Shanghai wasn’t the right first port of call in Asia. So, six weeks after I landed in Shanghai, Larry made the very prescient suggestion that we pivot to Hong Kong and use that as our base of operations, for all the reasons I enumerated earlier in the conversation. It was, characteristically for him, a great decision.

AMcDHow has the expansion of other contemporary Western galleries in Hong Kong shifted the business over the past decade? Has it helped build interest or expand the collector base?

NSHugely. More and more Western galleries have been coming to Asia, first maybe to participate in the art fair and then to think seriously about taking space.

The art fairs have been really influential. Take for example the transition from Art Hong Kong to Art Basel Hong Kong: Art Hong Kong had been a popular fair that generated a lot of interest in the region, and people would fly from across Asia to attend it, but Art Basel buying Art Hong Kong was a major signal that sent shock waves rippling across the continent. It was a quantum leap in terms of awareness, recognition, and interest. Hong Kong galleries were now visible on a global stage and Hong Kong’s fair was spoken of in the same context as Basel and Miami. You couldn’t imagine a bigger endorsement for contemporary art in Asia.

Today, the auction houses are incorporating Western art into their evening sales in Hong Kong in a way they never did before. That trend only started in the last two years, give or take. And all of this has led to an enormous groundswell of interest. The desire to collect Asian art in Asia continues, but collectors now have a wider scope.

AMcDBefore the onset of COVID, there was serious political unrest in Hong Kong. How did that affect the art economy? Did that instability make the challenges of the covid impact more complicated? Was the market in a place of uncertainty, or was it robust when COVID shut things down?

NSObviously the protests were a difficult time for Hong Kong, and COVID has presented an extended series of closures in the city, as it has everywhere in the world. Many people have suffered tremendously. The fairs aren’t happening and collectors aren’t traveling. Anecdotal evidence suggests that this has had a massive impact on the financial performance of galleries in town. That said, I feel fortunate that Gagosien was perhaps uniquely situated to confront the challenges of the past eighteen months. We’re an international business that had already been working with collectors in the region for over a decade before the protests started. We had also invested a lot in terms of preparing for the digital future of the art market. And collectors here have long been accustomed to buying art from social media platforms. Asia continues to be a growth story for us.

I think this is fundamentally due to the fact that people want to collect. People enjoy buying art and they enjoy sharing discoveries with their friends. The lockdown measures and lack of public gatherings haven’t changed that dynamic. People continue to be interested in collecting art as a way to understand themselves and the world around them.

AMcDSocial media and communication platforms are quite different throughout Asia. Would you touch a bit on how you communicate with clients and artists? How do these platforms factor into promotion and direct sales?

NSYou know, it’s not my personality type to begin with, but reaching out too directly to a collector and asking if they’re going to buy something is not a winning formula in Asia. It’s seen as aggressive. And oftentimes social media platforms play a very useful role in terms of sharing information with collectors or initiating a dialogue, but at a remove. That way, if they’re not interested they can pass on a work without feeling like there was pressure. And if they’re interested, it’s a very convenient and efficient way to keep in touch.

I very, very rarely email collectors in Asia. I can’t remember the last time I offered a painting by email. Almost all the business I do out here is done over WeChat, WhatsApp, Line, Kakao, and of course over the phone. Collectors will often want to talk about an acquisition before making a purchase, but I’ve found in general that collectors are very happy, if not relieved, to do business over social media platforms. It’s also important to bear in mind that this protocol has been established and facilitated by over a decade of face-to-face meetings across Asia. I look forward to having those meetings again when possible. There’s no substitute.

AMcDWhat roles do art fairs play? Are there any fairs in particular that you can speak about as examples of types of work offered, regional influence, or audience reach?

NSArt fairs are absolutely indispensable to our business here. It’s a wonderful way to connect with friends and meet new collectors, often through warm introductions by existing clients. The sharing of information through informal networks is a very well-established pattern in Asia. Most collectors have a group of friends who influence each other’s thinking and opine on what should and should not be acquired, and fairs are a logical extension of this; they’re an opportunity for people to get together with their friends, have dinner, and talk about what they might have seen. The further development of a healthy art market in Asia at least partly depends on the existence and expansion of fairs.

But like the countries themselves, the fairs in these different places each have their own unique character and identity. Art Basel Hong Kong is exceptional in that collectors from across Asia and indeed the world will come to Hong Kong for it—attendance is seen as compulsory for any serious Asian collector. Most other fairs tend to be heavily regional. So while some Japanese collectors will come to Taipei Dangdai, for example, our main focus in Taipei is to serve Taiwanese collectors who might not come to Hong Kong or who are just incredibly private.

AMcDWhat about West Bund and Art021?

NSFantastic fairs. They’ve set the standard for fairs in China and they’re truly international in scope and quality. Once we phase back to normal, Shanghai Art Week in November will feel a lot like Art Basel Hong Kong in March. It’s become a de facto destination for collectors from other Asian countries as well, and is of course underpinned by the enormous interest from within China itself.

AMcDIs that a new phenomenon, or has that been going on for a long time and it’s just building momentum now?

NSWest Bund and Art021 have been around for about five years, give or take, and they continue to go from strength to strength. Shanghai enjoys world-class programming at a growing number of extraordinary museums, including Long Museum, TANK Shanghai, the Centre Pompidou Shanghai, Yuz Museum Shanghai, and others still under construction. Galleries are continuing to proliferate. Taken together, I would wager that there are more cultural events happening in Shanghai during Art Week than in Zurich during the week before Art Basel. The last I heard, it was something like a hundred art events between the various openings and fairs. I’m sure it will continue to grow.

AMcDHow did the markets in Asia fare during the financial collapse that happened in November of 2008?

NSAsia largely sidestepped the global financial crisis of 2008. Investors here didn’t have as much exposure to the risky, synthetic financial products that triggered it. In fact, during that moment of profound instability, our business in Asia grew. And similarly with COVID, Asia has taken a radically different approach to dealing with the virus. Many collectors here had been through a similar cycle with the SARS virus in 2003, and I think they remembered what had happened to the economy. They recognized that artworks might be brought to market in this moment that would not otherwise be available to them.

AMcDWhat role do auctions play? How have the recent, highly produced online live auctions by Sotheby’s and Christie’s been received?

NSI have found the collectors I work with in Asia to be incredibly curious, passionate, and dedicated, but also pragmatic. Which is to say, it’s very difficult to gauge whether the theatricality of these online auctions and their production values are persuasive enough to spark buying. The online approach is entertaining and I can understand why it’s necessary at this moment, but I don’t think collecting decisions are being swayed by TV-style auctions. My impression is that Asian collectors never really took part in the pageantry of the evening sale anyway, and a vanishingly small percentage of people would be willing to travel from Beijing to New York to attend an auction in the first place. They’d much rather just bid on the phone or through their representative at the auction house.

AMcDWhat advice would you have for anyone who might be interested in starting an art business in Hong Kong? Or, looking back, what advice might you have given yourself ten years ago when you were starting out in Hong Kong?

NSI would encourage them to come. It amazes me that every morning I wake up and we’re still at the beginning. It’s been almost fourteen years for me personally, and I feel like we’re only scratching the surface of what’s possible in Asia. Hong Kong is the third-largest art market in the world behind New York and London, and will soon supplant London for good, if it hasn’t already. We’re still discovering the contours of what’s achievable here, and I find that enormously exciting, challenging, and rewarding.