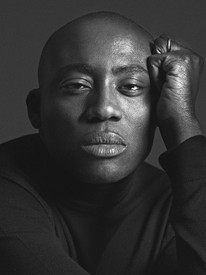

Derek Blasberg is a writer, fashion editor, and New York Times best-selling author. He has been with Gagosien since 2014, and is currently the executive editor of Gagosien Quarterly.

Derek BlasbergLet’s start at the beginning. Do you remember the first slide you ever saw?

Carsten HöllerWhen I was a boy growing up in Brussels, I took a bus to school, and the bus would drive by a home for the elderly. It was a freestanding red brick building in the middle of a green lawn, and on all four sides it had a super shiny steel slide that ended on a large picturesque lawn. Obviously, it was to save the elderly in case of a fire. But I just thought, “That’s brilliant, why isn’t this everywhere?” It stuck with me since. As a child you see it from a different perspective: “Wouldn’t that be fun to go down?” But sometimes I wonder why we only think slides are for fun and just for children. When I make slides and someone tells me that their children enjoyed it so much, I want to say: “You know, it’s not for children!”

DBHow did this particular commission come to you?

CHAnish asked me. I think, after they built the tower, [the former mayor of London] Boris Johnson was looking for a way to increase the revenue it generates. Anish and I met at the opening of the Prada Foundation in May 2015 and he asked if I would be interested, and I said I would be. What’s interesting for me, though, is that this is not a real collaboration. He did his part, which was to build the tower and then I did my part, which was to build the slide connected to it. It’s more about putting two things together, like a three-dimensional collage. This is intertwining ideas: we use the word “grafting,” which is a better word than collaboration. The slide is a new element that is both symbiotic and parasitic to the tower. It’s not fusing two artworks together, it’s about one holding the other, like a skeleton holds the body’s intestines in place.

DBDid you say yes immediately or did you take time to think about it?

CHI have been building slides since 1999 in many different contexts, and I’ve never said no to building one because I didn’t like the building. The opposite, actually, I find it interesting to make a statement about using slides everywhere. And this is a very good statement: it’s the tallest, longest slide in the world. It proposes the idea not only of the slide as a means of transportation, but also as a tool for introducing a moment of real madness into daily life. If slides were everywhere—if architects would listen to me and stop building only stairs, escalators, and elevators—it would be a different world.

When I make slides and someone tells me that their children enjoyed it so much, I want to say: “You know, it’s not for children!”

Carsten Höller

DBTell me how you conceived this design.

CHThe first thing I had to look at was the entrance and exit, and from there on you start to build it: the slide comes out and projects away from the structure and then comes back again, like a slightly deformed bed string from a used bed. At the beginning, it’s almost like an intimate relationship, where it pierces through the structure, then it leaves as far as you can possibly go, and then you come back for a tighter grip and an exit. There are a couple of “S” curves, which means you change direction and don’t come down too dizzy.

DBYou estimate that it will take roughly forty seconds from top to bottom. That sounds fast, but it will be the longest slide in the world.

CHThat’s quite long. It’s 178 meters [584 feet]. But, I haven’t had a slide experience where I thought, “That was too long!”

DBYou said earlier that slides should not just be for children. Do you think that this work will appeal to a large demographic?

CHThere are some technical restrictions: You have to be 1.3 meters high [51 inches tall] and there’s a weight limit. But, in principle, I like the idea of having as many different access points, artistically speaking, as possible. It’s not just a connoisseur artwork. It can be approached and used in multiple ways, by a child or someone with a different cultural background or someone who is into architecture more than art.

DBDo you think people will be scared?

CHTotally, yes. Strong fear and fun will be amalgamated in a way that leaves no space for anything in between. At the same time, in all its predictability, the slide has something comforting, prenatal, transformative. That’s why it’s different from rollercoasters, which I hate.

DBYou’re kidding!

CHNo, I hate those things! They scare me to death.

I haven’t had a slide experience where I thought, “That was too long!”

Carsten Höller

DBWhen did you start creating slides?

CHI had made an exhibition in 1996, that was called Glück, in Cologne, which is a word that translates into “happiness, luck and fortune,” in German. I wanted to make an exhibition that altered people’s mood in such a way that they all come out synchronized. Like when you go to the movies, and you see a group of people come out of the cinema who all look happy, or they all look sad. I always found that utterly fascinating. So, that show was an attempt to equalize people’s moods, and it had a hut with a roof that people could slide down from. But for that first slide they used a sled, so it wasn’t an independent slide like this one.

DBYour first real slide debuted in 1999.

CHYes, because I started to think about the combination of a slide’s functionality and the potential for madness. When it comes to using a slide, my favorite quote is from the French writer Roger Caillois. He speaks of vertigo as being “a kind of voluptuous panic upon an otherwise lucid mind.” I think that fits the experience of sliding.

DBWith a slide, you know what’s going to happen. You see where it goes.

CHThere’s absolutely no surprises, it’s almost technical as an experience. But you have to let go and give up all possible control to the powers of gravitation and construction.

DBI’m so fascinated to hear that you don’t like water parks. I thought it would be the dream job for you.

CHIt’s interesting to talk about fun, which I find a severely neglected topic in philosophy and all other mindful domains of our culture. It’s sort of discredited as something unintellectual or dirty, like watching soap operas and putting your intellect on hold. But fun is such a governing force in our lives and it has shaped evolution of human culture and society to such a degree that I think our attitude to it needs to be revisited. That’s the point of what I do, revisiting the idea of fun. Personally, I believe there’s something uncanny to it, since we clearly obey fun but fun itself seems to be governed by other forces.