Meredith Mendelsohn covers art and design for a variety of publications, including the New York Times, Architectural Digest, and Artsy. She recently contributed to a forthcoming monograph titled City of Lights: The Undiscovered New York Photographer Marvin E. Newman.

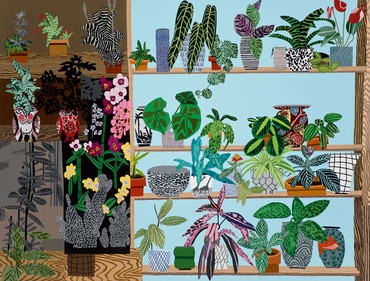

In an era when dazzling architecture is the art-world norm, and in a city where there’s no shortage of flash, the unassuming home of the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) in downtown Los Angeles can feel hidden in plain sight. Los Angeles artist Jonas Wood has changed that. Ever since December, when he covered MOCA’s 5,400-square-foot façade with a mural of verdant plants in decorative ceramic vessels, the building’s stretch of Grand Avenue has been decidedly sunnier. “It has completely changed the temperature outside the museum,” says the institution’s director, Philippe Vergne.

The mural grabs the attention of passersby but also humanizes Grand Avenue, a busy north-south corridor that is now one of the epicenters of LA’s cultural activity. While skyscrapers and office towers vie for attention with some of the city’s more muscular architectural attractions—the neighboring metal-clad Walt Disney Concert Hall and The Broad museum, with its dramatic concrete-and-fiberglass honeycomb façade—Wood’s mural immediately attracts the eye by transforming the building’s exterior. Rendered in Wood’s trademark style of flat intersecting planes bursting with pattern and color, the image is also a reminder of what’s inside the building. “This was really about bringing the museum outside,” says Vergne. “I always liked the idea that when you looked at ancient architecture in Greece or in Rome, it used to be polychrome and with time it became monochromatic. So for me it’s also a little bit about that. Let’s bring back some visual lust in the streets.”

Designed in the mid-1980s by Japanese architect Arata Isozaki, the somewhat traditional, red-sandstone-clad MOCA flagship, with its arched entryway and pared-down geometric façade, was funded as a redevelopment project to draw visitors and boost commercial activity along Grand Avenue. Adhering to height restrictions in place at the time, Isozaki situated most of the floors underground, including the galleries, which are illuminated by skylights. It hasn’t always been advantageous to be the unassuming introvert of the neighborhood, but it turns out that Isozaki inadvertently created a blank canvas. “We’d been having these conversations at MOCA about how curiously invisible our building is since much of it is actually below grade, and I was looking at it one day and I realized there’s more of it above grade than we think there is, but it just kind of disappears on that streetscape,” says Helen Molesworth, the museum’s chief curator. “So I wondered what if we drew attention to it in a different way, and I thought, you know what would look good there? A Jonas Wood. It was extremely intuitive.”

Fortunately for MOCA and the public, Wood agreed to the task. “The idea to do this was really smart because MOCA has an amazing permanent collection—there are like twenty-five Rothkos and thirty Rauschenbergs—and the building is very nondescript, and it’s almost like a subway station, where you have to go down the stairs,” says the forty-year-old Wood, who grew up on the East Coast and moved to LA in 2003. “They have a million people taking pictures in front of the mural now,” says Jonas, who modestly insists that any number of artists could have transformed the façade this successfully.

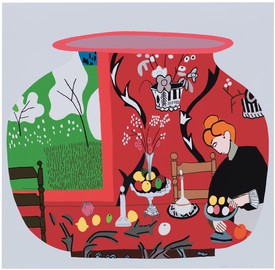

For MOCA’s façade, Wood proposed a version of his Still Life with Two Owls (2014), a complex canvas first exhibited in 2015 at Gagosien Hong Kong in a joint show with the Japanese-born ceramic artist Shio Kusaka, whom Wood is married to and whose pots appear in the painting. (The two have another joint show at the Voorlinden Museum in the Netherlands this fall.) While Wood usually works at a smaller scale, making paintings, prints, and drawings in the studio he shares with Kusaka, he’s no stranger to the large-scale format: in 2014 he created a billboard of potted plants for the High Line in New York, and another for the nonprofit organization LA><ART, whose brick façade he also painted. “One reason we chose him is that he can handle very different scales,” says Molesworth. “He can make a small print and then that can operate at the scale of a very large painting.” His flat, colorful figuration, which borrows a bit from the illustration aesthetic and saturated colors of ’60s Pop art, also lends itself to such an endeavor. “Even when he makes three-dimensional space you’re very aware of the flatness of the plane, which is particularly good for this kind of mural,” says Molesworth. “And then of course there is his palette, which is so bright, so sunny, so optimistic. And all of those things are really good for public space.”

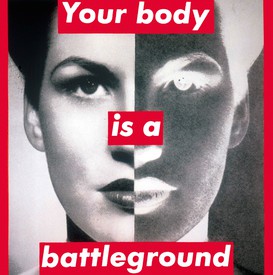

Wood changed the painting’s scale and swapped different parts of the canvas to present a continuous image of shelves and pots along the irregularly shaped wall, but the façade’s rocky face presented another set of challenges for the artist. The solution was a vinyl stickerlike material, which is heated up and then adhered to the surface. “We tested out a lot of different materials,” says Wood, referring to his collaboration with the fabricator and artist Eder Cetina, of the digital graphics firm Olson Visual, who has worked with countless artists, including for example Barbara Kruger, to transform artworks into murals. After Wood remade the painting, Cetina printed a digital image of it on vinyl strips, which were then painstakingly fitted together.

Wood, who lives in the city’s Westside with his wife and two kids (ages five and seven), grew up in Boston, attended college in upstate New York (where he got his BA in psychology with a minor in studio art), and then moved to Seattle to get his MFA in painting and drawing. There he met Kusaka, who was studying ceramics, and the two headed together to Los Angeles in 2003. “It was either New York or LA, and a friend of mine told us we could get jobs working for artists if we moved to LA.” Kusaka got a job working for the sculptor Charles Ray while Wood soon landed at the studio of Laura Owens, who was already recognized as one of the city’s most influential young artists. “I got to learn from someone who has a tremendous studio practice, but also who is open to painting lots of different things,” says Wood. “That was a big deal for me.”

That open-minded approach to subject matter has yielded a body of work that runs the gamut from still lifes, interiors, and landscapes to portraits, which include family members as well as sports figures (based on trading cards, one of Wood’s pictorial inspirations early on). What links his varied imagery is a continuity of style, a cheery graphic modernism softened by a slight quirkiness—an imperfect line, a skewed perspective—that feels highly personal, as though the way an object makes him feel is as important as the way it looks. “I paint what turns me on,” he says. And while traces of Owens’s style can sometimes be detected, the British-born Los Angelino David Hockney comes more to mind, with his abstracting take on sun-drenched suburban mid-century LA, as does Henri Matisse, whose flattened, decorative, allover approach prioritizes no part of the canvas over another. In Still Life with Two Owls, Wood’s use of pattern—the stripes of Kusaka’s ceramic pots, or the zigzagging lines of plant leaves—inevitably invokes Matisse’s groundbreaking use of pattern to add structure to an image and to harmoniously merge figuration and abstraction.

“Hockney was a big, big influence on me. He has that Renaissance ability to paint from life but also he’s also an inventor,” says Wood. “But I love Picasso and Braque and Matisse and Vuillard….And the thing about Hockney or Alex Katz or Lucian Freud or any of those people that I’m super into, they were into those modern painters, too. So I get to look at Matisse or Picasso through their work.” Given Wood’s deep involvement in the history of contemporary and modern art, his work seems like an especially fitting invitation to enter a museum. But the mural also reveals a viscerally Californian sensibility that makes it feel right for this spot. Wood’s sunny visions of houseplants, architectural pottery, and blue sky invoke a mid-century postwar moment when the new availability of steel meant bigger windows and more light, and when greater affluence meant more leisure time and the popularization of the indoor/outdoor lifestyle made fashionable in LA by such designers as Charles and Ray Eames. The reference feels culturally appropriate. The mural, perhaps coincidentally, also hints at a Japanese aesthetic: the generous use of black, the woodblock-print-like linearity, the wave pattern of Kusaka’s ceramics. It’s a fitting reference for a building designed by a Japanese architect in a neighborhood not far from the city’s historic Little Tokyo.

Still Life with Two Owls was actually sourced in part from an image of a shelf with plants and pottery from a 1970s House & Garden–type magazine, says Wood. “I usually use those and then replace about 70 percent of the plants and objects in them with things I’m interested in.” Kusaka’s patterned pots fill the shelves in the mural, while the two owls are renditions of figures in the couple’s collection by the late ceramicist Akio Takamori. The plants are a mix of Wood’s own (he has a lot of them, he says) and found images.

At the end of its run, in late 2017, the vinyl will be peeled off and disposed of, immortalized by its many appearances across social media, but Vergne and Molesworth hope to adorn the façade with a new mural by a different artist each year. “This thing that was invisible is now totally present. And it’s present in a very, very lively way,” says Molesworth. “I see people walking by and pointing at it and talking about it. For a lot of people it’s an Instagrammable moment.”

Artwork © Jonas Wood