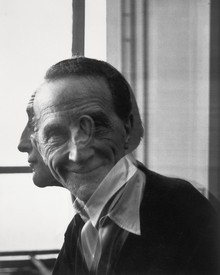

Walton Ford recasts, reverses, and rearranges the conventions of animal art. He is a devout researcher, responding to everything from Hollywood horror movies to Indian fables, medieval bestiaries, colonial hunting narratives, and zookeeper’s manuals. He grew up in the Hudson Valley, graduated from the Rhode Island School of Design, and currently lives and works in New York.

Stac an Armin

Fifty miles from the coast of Scotland, the rocky islands of the St Kilda archipelago bristle out of the North Atlantic like a shattered spine. Stac an Armin is one of these shards of stone. Gannets, puffins, petrels, and fulmars nest on the ledges of this volcanic spike.

In the mid-nineteenth century, the island people of St Kilda survived by eating eggs, chicks, and full-grown birds from the island’s cliffs. Travel to and from the mainland was dangerous and rarely attempted. Most islanders had never seen a tree, a horse, a painting, a staircase, or a book besides the Bible. They saw only St Kilda and her birds, storms, orcas, sharks, seals, and native sheep. Their preachers also taught them to see either God’s wrath or the devil’s hand manifested in the grim weather, disease, melancholy, and lusts engulfing them.

Around the same time, the great auk of the north Atlantic was nearing extinction. This goose-sized bird was a cousin of the puffin. A flightless bird, the great auk resembled a penguin, having evolved to do the same job—namely, to “fly” under water and catch fish. All the great auks around St Kilda had been slaughtered for their down so many years before that the islanders had no memory of them.

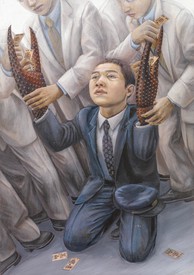

In July of 1840, five island men hunting birds on Stac an Armin found an auk asleep on a ledge. It was one of the last auks seen alive.

It was Malcolm McDonald who actually laid hold of the bird, and held it by the neck with his two hands, till others came up and tied its legs. It used to make a great noise, like that made by a gannet, but much louder, when shutting its mouth. It opened its mouth when any one came near it. It nearly cut the rope with its bill. A storm arose, and that, together with the size of the bird and the noise it made, caused them to think it was a witch. It was killed on the third day after it was caught, and McKinnon . . . was the most frightened of all the men, and advised the killing of it.1

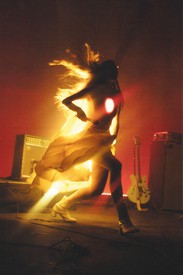

I wanted to imagine what this auk/witch would be doing in the minds of those men. What would a witches’ sabbath look like in the mind’s eye of these islanders? What insular sexual tension was made sinister by shouts from the pulpit? The young Lauchlan McKinnon, “the most frightened of all the men,” saw an unknown animal. In that animal he saw a fearsome female creature, a woman assuming animal form, a lascivious witch in league with the devil and the animal world. He saw his frenzied fears made flesh to be killed and forgotten.

black-tailed, dusky, prairie, banded rock, and massasauga, all coiling and striking among cactus and sage.

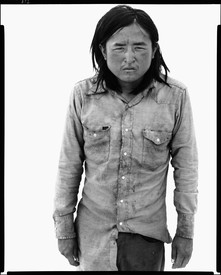

Cabeza de Vaca

In 1528, Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca got lost. He wandered, lost, for the next eight years, across what we now call the American Southwest. He was one of an expedition of over 300 Spaniards who waded behind Pánfilo de Narváez into the tangled swamps of Florida in search of golden cities. Bushwhacking away from their ships, they started to die. They built rafts and drowned. They starved and died of exposure. They were captured, killed, or enslaved by the native peoples. Cabeza de Vaca was one of only four survivors to finally stagger into Mexico.

Everywhere Cabeza de Vaca walked during his trek, he would have met rattlesnakes. There are no rattlesnakes in the old world. A Spaniard could not have dreamt of such a creature. In Florida, he would have been startled by pug-faced eastern diamondbacks, seven feet long; swift, mustard and rust-colored timber rattlers; and diminutive pygmy rattlesnakes buzzing like insects underfoot. Farther west, he would have confronted whiplash-angry western diamondbacks the color of dust. Black-tailed, dusky, prairie, banded rock, and massasauga, all coiling and striking among cactus and sage. All the way from Florida to Mexico, species after species—shape, pattern, and size shifting and changing.

I have painted Cabeza de Vaca’s delirium—a vision of fear and enormity.

Toward the end of his ordeal, Cabeza de Vaca began to see abandoned native villages, burned and looted. He knew he was nearing his Christian countrymen. By the time he finally met a mounted party of Spaniards he had become a revered healer among the native peoples, a mystic, bearded and browned. He was a shocking sight to his countrymen, who promptly enslaved his native companions. A few months later, Cabeza de Vaca was on a ship bound for Lisbon.

1J. A. Harvie-Brown and T. E. Buckley, A Vertebrate Fauna of the Outer Hebrides (Edinburgh: David Douglas, 1889), p. 159.

Artwork © Walton Ford