Mike Stinavage is a writer and waste specialist from Michigan. During his political science masters program at CUNY Graduate Center, he was awarded Fulbright and Martin Kriesberg fellowships to research the politics of waste in Northern Spain. He currently coordinates a European project on biowaste policy and writes fiction in Pamplona, Spain.

Below the Athens Concert Hall and Conference Centre is, unsurprisingly, its basement, and below that is an immense concrete vault. Unlike the conference center, which, in early September, was crowded with attendees of the 11th International Aerosol Conference, the underground vault remains silent except for the hum of the utility pipes tethered to the high ceiling above. This is where one can find the studio of the Greek theater director Dimitris Papaioannou.

On one side of the studio is the characteristic disarray of a sculptor’s or carpenter’s studio during lunch break. Two aisles of materials stacked high overhead run the length of the space. Scattered across a workbench are clamps, power drills, paintbrushes, and adhesives. On the surrounding shelves are the foam mats, tubing, wood panels, floorboard slats, and sheets of fiberglass typical of Papaioannou’s work. Toward the end of the second aisle, the rocklike Styrofoam blocks from the Sisyphean struggle in Transverse Orientation (2021) are wrapped neatly in cellophane.

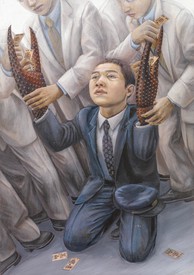

Between the aisles and the rehearsal stage is a changing room. Because there are no walls, one can easily see the portable wardrobe, a line of neatly paired shoes, and two glass terrariums, bulblike in shape, on which perch the mock octopi of Ink, Papaioannou’s most recent work. Opposite the stage are the kind of full-length mirrors typical of dance studios.

Without windows and little air circulation, it’s easy to lose track of time. Against the brutality of the space, Papaioannou and his technical crew are the source of warmth. “This is the space we were given,” he said, almost reluctantly, as I looked at the image board of Spanish bullfighters, details of red and black figures on amphorae, and two studies by Picasso, Two Brothers (1905) and Figure of Young Man (1906), in which prepubescent boys, not yet contoured by musculature or hair, stand nude.

This is where Transverse Orientation was made. In the months before the pandemic, Papaioannou and his collaborators had just set the structure of the piece. When Greece went into lockdown, work halted abruptly, with the crew uncertain whether the piece would become another casualty of the pandemic. “What is surprising,” Papaioannou observes, “is that the production survived. We kept thinking: if the pandemic kills it, it’s going to be killed. But somehow everyone was committed to trying to do it.”

For Papaioannou and his collaborator Šuka Horn, the months of lockdown were not unproductive. They quietly came to the studio to make a new piece, a duet titled Ink. When the lockdown ended and all work resumed, Transverse Orientation underwent a revision: “When I came back, I removed myself. The piece lost its narrator. This is a dramatic change, I think. It gave rise to humor. It became more open to surrealism and free-form association.”

Papaioannou speaks with slow precision. He selects his words with the carefulness with which the materials of his studio are stored. When asked a meandering question, he is quick to ask for clarification or to admit that he simply doesn’t understand. In those moments, a sense of artifice, of boyish pleasure, enters his expression. When asked a clear question, he patiently chooses his words and tactfully maneuvers ambiguities to provide a clear response.

After debuting in Lyon, France, in 2021, Transverse Orientation arrives in the United States in November 2022, when it opens at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. The tour closes in Stanford, California, the following month. The pandemic has shaped both the logistics of the piece and its content. The year-and-a half-long tour was redesigned three times. For Papaioannou, the outcome was not exactly untoward: “For me I have benefited from having more time to think about the piece. Generally, those interruptions for me are very welcome because I get to rethink a little bit what I am doing.”

Transverse Orientation, like Papaioannou’s previous work, The Great Tamer (2017), may appear to be a nonlinear and noncumulative assortment of visual delicacies, but however unrelated the sequences may seem, there is a distinct logic and a general narrative arc. “The sequences are being built by experimenting and playing in the studio. By throwing materials and ideas to the performers. By trying them out with our bodies. By selecting a lot of stuff that I find even remotely interesting, and then trying to revisit it after it has been born. Some of those moments, when you see them, you can imagine that they could work together and so you put them together, but they don’t work so you try again. Those small stars create a constellation. I have to be alert to what I find interesting.”

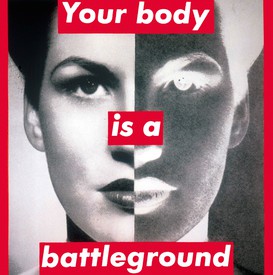

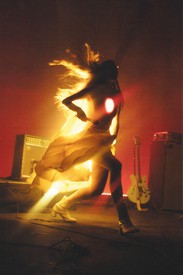

Transverse Orientation, including its moments of horror and repulsion, is a rich visual repertoire that mixes recognizable images from Greek myths and canonical portraiture. “The basic symbol is the bull, which is unhinged masculinity. The wonderful and dangerous elements of masculine force that have to be tamed.” The bull comes in many forms. Early in the piece, the dancers struggle to restrain, and simultaneously animate, a life-size puppet bull. Then, throughout the piece, a minotaur appears and disappears among his human counterparts. “It’s a wonderful image, a male body with a bull’s head, and a wonderful fight—it’s so clearly and beautifully and so obviously that battle with our animal self.”

Under the stage lights, Papaioannou’s devious play with unhinged masculinity is embodied by youth and beauty. What is seen onstage is an enchanting abstraction that moves backward toward atavism instead of forward toward activism; there is no value judgment. The consequences of masculinity, homoerotic and otherwise, are not embodied but explored. “I have a fixation on Sisyphean concepts onstage, that people are doing things that they seem to have been doing for eternity,” Papaioannou said. “Youth, for me, is a fixation. A beautiful youthful body that has to go through a lot of discoveries—that is another archetypical idea.”

If we rack our brains long enough, the struggle becomes meta: the primary challenge is no longer the struggle itself (animalistic urges, insecurities, cardinal sins, and so on) but the struggle of representing that struggle. A distant, more diluted, and less personal struggle thereby replaces the primary one. Yet even if we fall into this tempting deep read of Sisyphean challenges at large, we may not, sadly enough, accomplish much. The rock will come tumbling downward.

What is accomplished, according to Papaioannou, is deception. “I invite the audience into the ridiculousness, always reminding them that if there is magic happening, it’s only happening because they want magic as well, not only because we can do it. Because it’s all a lie. But beauty is there. Aphrodite [in Transverse Orientation] becomes a fountain, which is funny and dark, which is still extremely beautiful and extremely sexy, but it’s extremely fake.”

He pauses for a moment, and then continues: “What is continuously fascinating for me are chimeras. To create the illusion of the combination of the animal and the man, of a man and a woman, of a rearranged human body, to suggest images that everybody knows don’t exist but to suggest them in a way that people believe that it is there—this is a wonderful game for an illusionist. And another shortcut to human connection, because we somehow identify with it.”

For Papaioannou, there isn’t much more than a month between the closing of one international tour and the opening of the next. Ink, which has already debuted in Europe, will begin its world tour in Greece in January 2023. The new iteration will be distinct: the piece has been outfitted with a new finale, a new costume design, and new sound. “I started from a very happy place with a very happy collaboration with Šuka Horn and all this darkness came out of myself. I couldn’t believe it. I was very happy when I was working on Ink. One of the happiest periods of my life. The work that came out is almost psychological.” He then offered, “I think it’s about desire.”

This could be the last piece from Papaioannou for a while: “After Ink I don’t have more projects. I hope I will stop and take time off. Maybe a year. In the creative process,” he said, looking at an undefinable point before him, “I am asking myself, life, and the studio, secretly, what am I looking for. And I believe that when I like something that I see, it is what I’m looking for.”

“The goal,” he said over lunch the next day, “should never be to not be a monster.”

Traverse Orientation, BAM Howard Gilman Opera House, New York, November 7–11, 2022

Traverse Orientation, Stanford Memorial Auditorium, California, December 9–10, 2022