Dorothy Spears has written regularly for the New York Times for years. An anthology she edited, Flight Patterns: A Century of Stories About Flying, was published by Open City Books/Grove Press in 2009. She is currently finishing a memoir, Front Desk Girl, about coming of age in the late 1980s, when she worked for the late art dealer Leo Castelli.

Mark Tansey was brushing liquid graphite onto polyurethaned rag paper, which he was then imprinting with crumpled news articles, when one image stood out to him. “It looked like rock; it looked like water; it looked like foliage,” he recalled in a recent interview.1 “It was Yosemite.”

The finished liquid graphite sketch, Yosemite (2021), was exhibited at Gagosien, New York, in late 2021, along with a selection of work Tansey had made using the same process. But the particular image of Yosemite, whose richly detailed but variable topography suggests, at once, an aerial map, a craggy rock face, cascading water, a cave’s interior, and trees—while also reminding Tansey of the California national park he loved visiting with his parents as a child—has now inspired his oil study Sunstruck (Study for About) (2022).

Mountains and caves—and specifically Plato’s Cave—have been ongoing themes in Tansey’s paintings. And Tansey’s fascination with the trope of the sunstruck philosopher dates to some of his earliest work. In his etching Sunstruck Philosopher (Allegory of the Cave) (1980), a bearded man, outfitted in typical modern-day, Western attire, emerges from the darkness of a cave into bright sunlight, while holding—somewhat improbably—an umbrella. The alleged philosopher’s posture is hunched, as if he’s sneaking away, and his expression as he eyes the viewer over his shoulder looks almost embarrassed, suggesting that Tansey is poking fun at his supposed authority.

Tansey’s sunstruck—or blinded—philosopher points to a host of historical references, from the ancient Didymus to Galileo, who lost his sight in old age, and who is often rumored—falsely—to have gone blind when he turned his telescope toward the sun. Friedrich Nietzsche also suffered from nearsightedness that left him nearly blind. A line in Thus Spake Zarathustra (1883–85) speaks to the predicament of Tansey’s male figure: “And the blindness of the blind one, and his seeking and groping, shall yet testify to the power of the sun into which he hath gazed.”2 And then there is Tansey’s own father, who, during one of the family’s long-ago visits to Yosemite, fell victim to a prank when someone reversed the signs in the park. “He got lost,” remembers Tansey. Then, upon finding his wife, he said, “There’s my referent.” Tansey recalls responding, “From lost to found.”3

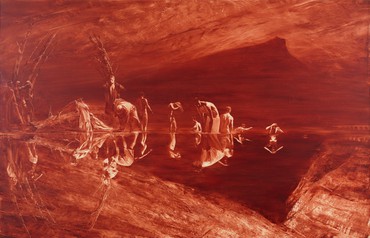

In Mont Sainte-Victoire (1987), Tansey imbues references to Paul Cezanne’s famous bathers and Mont Sainte-Victoire in Provence, France, with allusions to the lessons learned in Plato’s ancient cave, revealing his longstanding fascination with perception, and with how we as humans come to know—or think we know—what we know, while navigating the dizzying, and often conflicting, views of the world around us. But here again, there is a sense of disconnect between the bathers, who look tentative and self-conscious, and the figures in military dress on the left.

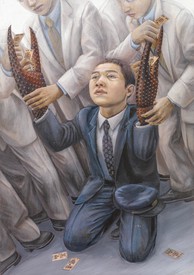

In Shades (2001), a trio of early humans in a cave crouch around the glowing embers of a fire, one warming his hands and another poking the flames with a stick as a more modern-looking female figure leans forward, bearing a large palm frond—rather absurdly—on her back. The vastly magnified and abstracted shadow of the frond on the cave’s wall, which resembles an eye, calls to mind the shadows on the walls of Plato’s Cave, as if to suggest that the way forward, or outside this single-minded realm of thought, is in recognizing that even this most iconic human invention—fire—was created through a combination of human senses, including vision and touch.

Duet (2004) builds upon this premise while citing the visual paradox of the Necker cube. In this painting, a female figure on the right seems to be planting her right foot inside—and simultaneously to be emerging from—a deep fissure in a rock face, which could also be read as a cave. As her left foot gains a toehold, she appears to be gripping cracks in the sheer rock face—which looks almost vertical—as if to pull herself up with her hands. Meanwhile, across an almost-Cubist configuration of rocks and surfaces, a male figure on the left climbs, if not necessarily sideways, toward a very different summit. Whether this is meant to imply that a climb is not always an ascent, or that sometimes “up” can feel more like sideways, is debatable. But what is clear is Tansey’s continued evocation of Western philosophy and its unresolved dilemmas. In the case of the Necker cube, an optical illusion proposes two possible orientations for a single image. In Duet, the figures’ shadows—which result from two opposing light sources—allow the rocks to be seen, simultaneously, as protruding and receding.

In Trefoil (2009) and Hedge (2011), Tansey disorients us further by inviting us to look at mountainous landscapes from different orientations. Each work provides an alternate point of view and alternative details within the image. Tansey seems to be asking us to consider—both literally and philosophically—multiple perspectives.

Abstract artists including Jackson Pollock and Helen Frankenthaler famously moved their paintings around on the floor to see them from different angles. George Baselitz painted—and hung—many of his images “upside down.” Even Roy Lichtenstein, whose paintings were mostly figurative, invented an easel he could pivot upside down or sideways in his studio, the better to distance himself from rote, literal readings of his work and see it abstractly, in terms of composition and color.4 The physical reorientation of artworks wrests familiar associations from our mind’s eye, allowing us to “unsee” certain details and see others from a fresher, and hopefully equally engaging, point of view. It also allows artists to equalize, both literally and figuratively, various compositional elements so that no single image or interpretation dominates.

But Tansey takes these reversals and upheavals to a whole new level. In addition to optics and visual imagery, he is fascinated by the metaphysics of multiple points of view. His disorientations pose a succession of questions: What are we as viewers looking at, and how do we know that what we perceive is real, and what should we believe, and, last but not least, how do we even feel about it? In other words, Tansey’s paintings urge us to examine our own experiences and perceptions in looking, an approach that points to the philosophical principles of not only epistemology but also phenomenology, which is defined as a study of “conscious experience as experienced from the subjective or first-person point of view.”5

In Reverb (2017), for example, we see a wall of portraits featuring couples, many of which include Woody Allen. The couples’ hand gestures make them appear engaged in animated conversations, and the presence of Allen makes their voices feel almost audible. To the right of the portrait wall stands a young couple. The woman holds a drink, her face and hand framed by a pair of mirrors so that her gaze meets the viewer, and her companion stands beside her, speaking his point, his disembodied hand gesticulating in the mirror. The suggestion of speaking voices in paint, which is echoed in the painting’s title, indicates a conscious attempt on Tansey’s part to visualize the audible, or at the very least to explore the sensory overlap between seeing and hearing.

the process of painting, being textural . . . the adding of darks and subtracting of lights, is basically finger painting in the cave painting tradition.

Mark Tansey

Tansey’s recent oil study, Sunstruck (Study for About), takes this crossing over in a slightly different direction, visualizing the tactile: as the male figure looks out in sunlight, the female figure seems to be handling cloth folds. These sensory crossovers could be interpreted as painted versions of synesthesia, an intermingling of the senses that characterizes poems by French Symbolists Charles Baudelaire and Arthur Rimbaud. Tansey sees these crossovers, or intermingling, as an aesthetic opportunity. “The crossover of eye, mind, hand,” he said, “the blending of all the senses, speaks to our intelligence, which is not quantifiable. The senses work together. And art’s in that realm.”6

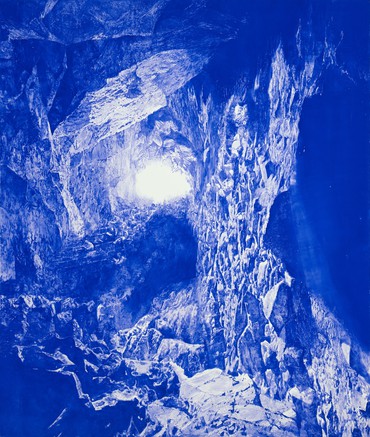

Sunstruck, painted in Tansey’s signature monochrome blue, excavates these ongoing fascinations and themes while signaling a remarkable new shift in his practice. The first work Tansey has made using one of his own drawings as a prompt, Sunstruck was not produced with crumpled paper. Rather, it creates that illusion, like a projection on the wall of cave—Plato’s Cave—and instead offers a painted facsimile of Yosemite’s fractured, craggy texture.

While looking at Sunstruck, Tansey said, “the viewer might become aware that the process of painting, being textural, the scratching and scraping of highlights, the adding of darks and subtracting of lights, is basically finger painting in the cave painting tradition.”7 In his evocation of finger painting, Tansey has not only abandoned his former way of making images. He’s abandoned himself to his process. For two to three months, during what he called the “copious, compulsive” making of Sunstruck, he said, with a chuckle, “I was living in that thing, and it was dizzying.”8

Perhaps the farther the tradition of painting moves ahead, the more it reverts to its essential cave origins. Perhaps the fractured surfaces and dizzying effects on such full display in Duet, Trefoil, Hedge, and Sunstruck represent time itself, so crumpled and contorted by history that the future and the past are almost touching. The writing on the wall, so to speak, is that this human endeavor we call painting requires the artist’s hand to interact with their eyes and mind as they explore the intrinsic physical properties of texture, groping for fissures or weak points, the better to understand them.

1Mark Tansey, telephone conversation with the author, April 5, 2023.

2Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spake Zarathustra, trans. Michael Hulse (Kendal, UK: Notting Hill Editions, 2022), p. 116.

3Tansey, telephone conversation with the author, April 5, 2023.

4Dorothy Lichtenstein, telephone interview with the author, January 26, 2014.

5David Woodruff Smith, “Phenomenology,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. Edward N. Zalta (Summer 2018), available online at https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2018/entries/phenomenology/.

6Tansey, telephone conversation with the author, April 5, 2023.

7Ibid.

8Ibid.

Artwork © Mark Tansey